3. Approach to Learning Standards, Content, Pedagogy,and Assessment

Chapter 1 articulated the Aims of School Education for this NCF which in turn were derived from

the vision and purposes of education outlined in NEP 2020. Chapter 2 detailed the four-Stage

design of schooling as recommended by NEP 2020.

This Chapter describes the approach taken by the NCF towards defining Learning Standards, selection of content, methods of teaching, and assessments to achieve these Aims in the context of the four-Stage schooling structure.

Education can be seen both as a process and as an outcome. When we view education as an outcome, we think about a student’s achievement of the desirable knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions as derived from the Aims of School Education. To bring clarity to all stakeholders on what students must achieve in schools, this NCF has articulated these desired educational achievements as Learning Standards.

‘Goal clarity’ or ‘clarity of objectives’ is a critical element for success in any endeavour; Learning Standards are intended to provide such clarity in school education to all participants and stakeholders — Teachers, students, educational functionaries, parents, and society as a whole. While providing and having such clarity has many aspects, three things are critical:

a. Any such ‘objective’ must be at a level of detail and time-horizon that the person using it should be able to relate to it and to draw relevant actions. For example, a Preparatory Stage Language Teacher would require goals that are to be achieved by the end of the Stage in Language and only having goals at the end of schooling will not be helpful to them; most parents would be able relate to goals that are for the particular age of their child and would find it difficult to relate to the Aims of Education as goals in a useful manner.

b. All such ‘objectives’ must be derived from the Aims of Education and together must achieve the Aims — this is operationalised by the process of ‘rigorous flow-down’ as mentioned later in this chapter.

c. The entire set of ‘objectives’ must be cogent, consistent, and connected, which would be essential to achieving the Aims.

These objectives, starting from Aims of School Education, are referred to as Learning Standards in the NCF.

The first section below defines a few terms used in this NCF in the context of Learning Standards and then gives an approach to arriving at the Learning Standards.

3.1.1 Definitions

*a. Aims of School Education: *Aims are educational vision statements that give broad direction to all deliberate efforts of educational systems — curriculum development, institutional arrangements, funding and financing, people’s capacities, and so on. Aims of School Education are usually directed by education policy documents. The NCF has derived the Aims of Education from NEP 2020 and these Aims were articulated in Chapter 1. These Aims of Education are to be achieved through the gaining and development of Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions, which guide the Aims within each of the subjects/areas of study.

b. Curricular Goals: Curricular Goals are statements that give directions to curriculum development and implementation. They are derived from Aims and are specific to a Stage in education (e.g., the Foundational Stage). This NCF, which would guide the development of all curricula, lists and the states the Curricular Goals for each Stage. For example, ‘Develops effective communication skills for day-to-day interactions in two languages’ is such a Curricular Goal for the Foundational Stage.

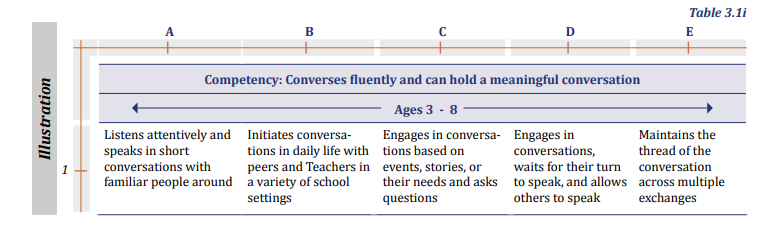

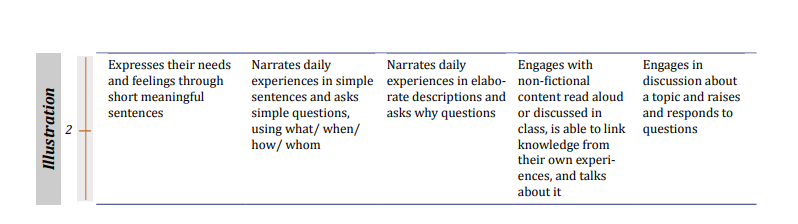

c. Competencies: Competencies are learning achievements that are observable and can be assessed systematically. These Competencies are derived from the Curricular Goals and are expected to be attained by the end of a Stage. Competencies are articulated in Curriculum Frameworks including this NCF. However, curriculum developers can adapt and modify the Competencies to address specific contexts for which the curriculum is being developed. The following are examples of some of the Competencies derived for the above Curricular Goal in this NCF — ‘Converses fluently and can hold a meaningful conversation’ and ‘Understands oral instructions for a complex task and gives clear oral instructions for the same to others.’

d. Learning Outcomes: Competencies are attained over a period of time. Therefore, interim markers of learning achievements are needed so that Teachers can observe and track learning and respond to the needs of learners continually. These interim markers are called Learning Outcomes. Thus, Learning Outcomes are granular milestones of learning and usually progress in a sequence leading to the attainment of a Competency. Learning Outcomes enable Teachers to plan their content, pedagogy, and assessment towards achieving specific Competencies. Curriculum developers and Teachers should have the autonomy to define Learning Outcomes as appropriate to their classroom contexts, while maintaining clear connection to the Competencies.

The following table is an example of Learning Outcomes derived for the Competency ‘Converses fluently and can hold a meaningful conversation’ in the Foundational Stage:

3.1.2 From Aims to Learning Outcomes

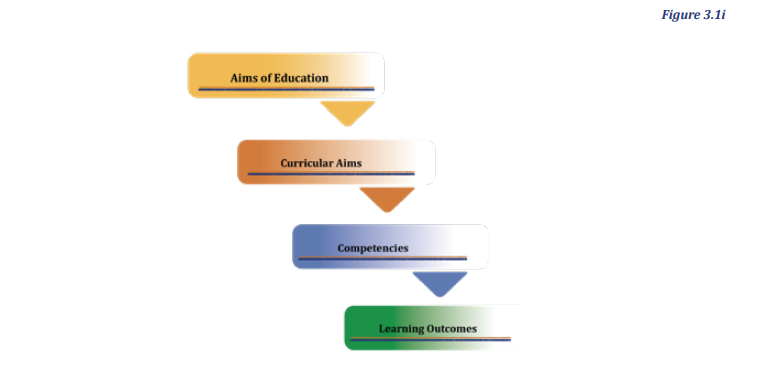

This NCF strongly emphasises the importance of the clear ‘flow-down’ that must connect Aims to Curricular Goals to Competencies to Learning Outcomes. Each set must emanate from the immediate level above while ensuring full coverage of the objectives at that higher level.

This is a process of ‘breaking down and converting’ relatively abstract and consolidated notions to more concrete components in order to make them useable in the practice of education. This process, including other considerations that must be accounted for in this ‘flow-down,’ are described in this Chapter. It is only such coherence, coverage, and connection arising from a rigorous flow-down, from Aims to Learning Outcomes, which can align syllabus, content, pedagogical practices, institutional culture, and more to achieving what we desire from education. This is simply because, in the everyday life of the Teacher and institutions, efforts are (or should be) made towards achieving very specific, observable, and short-period learning objectives which are marked as Learning Outcomes. These Learning Outcomes arise from the process of flow-down described below. They guide the trajectory of educational efforts towards the attainment of Competencies, which in turn accumulate to Curricular Goals. When the achievement of the Learning Outcomes, Competencies, and Curricular Goals are all taken together, they achieve the relevant Aims of Education.

NEP 2020 has articulated the vision and purpose of education. This NCF has drawn the Aims of School Education from this vision, which informs the knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions that must be developed in students in order to achieve the Aims of education. The aforementioned desirable knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions are thereby reflected in the Aims of each subject of study and also in the recommended school culture and practices.

*The Curricular Goals are, in turn, derived from the Aims of Education, along with other relevant considerations. The Competencies are then drawn from these Curricular Goals, and the Learning Outcomes from those Competencies. *

It must be noted that the Competencies given in this NCF are illustrative and may be modified by curriculum developers to achieve the Curricular Goals more optimally, based on their context.

Thus, curriculum developers should carefully consider the set of Competencies in the NCF and use these after making relevant changes where and if required. Given the relative stability and cross-cutting relevance of Competencies across contexts (and time), there may be fewer requirements for changes in the Competencies articulated in the NCF. However, decisions on this matter should be carefully considered by curriculum developers.

The Learning Outcomes can often be more contextual and will, therefore, require close attention and contextualisation for the curriculum or syllabus being developed.

Thus, the States and their relevant institutions, and other institutions responsible for curriculum and syllabus development, would need to conduct such a flow-down to arrive at a full set of Learning Standards for their use.

3.1.2.1 From Aims to Curricular Goals

The Aims of School Education, as envisaged in Chapter 1, give direction to the intended educational achievements for the four School Stages, through the Aims of each subject. As mentioned earlier, Curricular Goals to achieve these Aims are stage specific.

In this NCF, Curricular Goals for the Foundational Stage are defined for the different domains of development. It is appropriate that, at the Foundational Stage, the curriculum is closely aligned with the domains of child development. From the Preparatory Stage onwards, the Curricular Goals are defined for specific Curricular Areas. These Curricular Areas have been enumerated in Chapter 1 along with their aims.

While the Aims of Education are the primary source for the Stage-specific Curricular Goals, there are two other kinds of considerations in arriving at their articulation. The Curricular Goals are arrived at by considering:

a. the Aims of School Education, as articulated in the NCF (Part A, Chapter 1)

b. the Nature of Knowledge relevant to the Curricular Area

c. Age appropriateness specific to the Stage of schooling The Aims of School Education flow-down into the Curricular Goals. More specifically, the Curricular Goals are arrived at from the desirable Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions within the Aims that are relevant to the Curricular Area, and which would contribute to achieving those Aims.

3.1.2.2 From Curricular Goals to Competencies

The four main considerations for arriving at the list of Competencies are:

a. Curricular Goals, which flow-down into Competencies

b. Research appropriate for the Stage and Curricular Area that informs the choice of content, pedagogy, and assessment

c. Experience of various educational efforts in the country

d. Our context, which includes resource availability, time availability, and institutional and Teachers’ capacities

Each Stage has its own specific considerations regarding student’s development and the increasing complexity of concepts and requirements of capacities (elaborated upon in Part A, Chapter 2). These considerations, in turn, have an impact on the choices of Competencies within each Curricular Goal.

All stakeholders in school education should have clarity on the Competencies that are expected to be achieved. Keeping track of progress in the attainment of these Competencies for every student would allow school systems to ensure that all students receive appropriate learning opportunities towards reaching the Curricular Goals of the NCF.

3.1.2.3 From Competencies to Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes are interim markers of learning achievement towards the attainment of Competencies. They are defined based on the specifics of the socio-cultural contexts, the materials and resources available, and the contingencies of the classroom. A set of illustrative Learning Outcomes have been defined in this NCF, based on the broad understanding of the context of our education system.

These Learning Outcomes need to be seen as enabling guidelines for Teachers and school leaders and not as constraining demands on them. They must have the autonomy to reimagine the Learning Outcomes based on their contexts.

3.1.3 Nested Learning Standards

In the Curricular Areas of Art Education and Physical Education and Well-being, this NCF has defined Nested Learning Standards. These Curricular Areas have been given due attention in terms of specifying clear Learning Standards that outline the expected learning achievements of students. To achieve these Learning Standards, particularly at the Middle and Secondary Stages, schools would need specialist Teachers and resources (such as playgrounds and equipment).

Giving due consideration to the time schools might require to make such Teachers and resources available, the Learning Standards for these two Curricular Areas have been defined as two sets. The first set, called Learning Standards —1, details the full range of Curricular Goals and Competencies to achieve the educational aims of the Curricular Area. These should be accomplished by all schools as soon as they add the required resources. Nested within this is a subset called Learning Standards — 2. These should be accomplished by all schools from the very initiation of the implementation of this NCF.

Section 3.2 - Approach to Curriculum Content

Content of the curriculum will be contained in and manifest directly in the various resources and materials used in the teaching-learning process, including:

a. Books: for example, textbooks, workbooks, playbooks, and any other kinds of books and their extracts

b. Other kinds of TLM: for example, toys, puzzles, technology-based material including videos, and experimental kits

c. Learning environment: for example, classroom space, activities in the local environment, and engagement with the community. The learning environment of students must be safe, inclusive, and stimulating.

Developing books (including textbooks) must follow a rigorous process based on an appropriate syllabus. Carefully selected TLMs play an essential role in all classrooms. The arrangement and organisation of the learning environment is also important across all Stages, and especially in the Foundational and Preparatory Stages.

3.2.1 Content Selection

This section describes the broad approach for selecting appropriate curricular content. More specific considerations for choosing content within particular curricular areas are elaborated upon in their respective chapters.

Curricular Goals, Competencies, and Learning Outcomes give clear direction as to what content is to be used for creating learning experiences for students.

Concepts formed in the Foundational and Preparatory Stages are largely perceptive (e.g., colour as visually discriminated) and practical (e.g., spoon used as a lever to open a tin cover, money to buy things in a shop), but not theoretical (e.g., colour as a spectrum of light, lever as a simple machine, or money as a medium of exchange). Exploring the theories behind the perceptive and practical concepts is expected in the Middle and Secondary Stages of schooling. Choices of content for each Stage must be based on these considerations.

Content in the Foundational and Preparatory Stages should be derived from children’s life experiences. It should also reflect the cultural, geographical, and social context in which the child is developing and growing. As students move through the Middle and Secondary Stages, content can move away from the familiar and include ideas and theories not necessarily represented in the immediate environment.

Content should be tied to capacities and values that students need to develop through the Stages of schooling. Special care should be taken to avoid the promotion of stereotypes.

These are general principles of content selection; subsequent chapters on Curricular Areas describe the specifics.

3.2.2 Textbooks

3.2.2.1 Role of Textbooks

Textbooks have been given great importance in Indian school education. In fact, it is a widely shared notion that, in practice, in too many of our schools and in the culture of our education system, textbooks stand in for all of the curriculum and syllabus, and the use and importance of most other materials and resources fades in comparison to textbooks. This is unhealthy and unhelpful for developing a robust system of school education.

This NCF has emphasised the achievement of Learning Standards as the central purpose of schooling. This emphasis signals a desirable shift in the role of textbooks. The current practice of ‘covering’ the textbook as the focus of classroom interaction should be avoided. Instead, the focus of classroom interactions should be the achievement of specific learning outcomes, and textbooks are one of the many resources available for Teachers and students for achieving the Learning Outcomes. Some important considerations regarding textbooks include:

a. Reduction in ‘textbook centricity’: As mentioned, our education is over-dependent on textbooks — this must change. Other kinds of TLMs, other kinds of books, and the surrounding environment must be fully utilised.

b. Expansive and inclusive notion of textbook: The sharp distinction between textbooks, workbooks, playbooks, and other kinds of books is suboptimal from a student’s perspective. The content and the form must be designed from a lens of ‘what will get the student to learn better’, and not from a textbook definition of ‘textbooks’.

c. Availability of multiple textbooks: Even the best of textbooks have their limitations. So, from a perspective of improving learning, it will be more effective to have multiple textbooks made available for the same subject and class, which can be compared and selected by school systems (or schools), and some may even choose to use more than one textbook. [NEP 2020, 4.31]

d. Quality of textbooks must be high: Students deserve textbooks with high design and production values with respect to both content and form. The design, layout, and illustrations all matter for ensuring quality, as does the final printing and production.

e. Cost of textbooks: The public system does and should make available textbooks free to all students. However, the cost of textbooks matters [NEP 2020, 4.32] and so must be optimised. Since textbooks have the connotation of being mandatory, this should not be used for profiteering by some publishers.

3.2.2.2 Key Principles of Textbook Design

With these important basics in place, the principles and process of textbook development are mentioned below.

a. Curriculum Principle: The textbook should be designed specifically to achieve the Competencies for the Stage and the Learning Outcomes for the Grade. Textbook developers and designers should not only be aware of the Competencies of the particular domain or Curricular Area for which the textbook is being developed, but also the Competencies for the whole Stage. This would allow them to bring in horizontal connections across the domains and curricular areas of the Stage.

b. Values Principle: The content chosen in the textbooks should also reflect the desirable values and dispositions articulated by the NCF. While values are often not explicitly taught, the school culture and environment should embody the desirable values. In addition, the content in textbooks play an important role in reflecting these values. For example, compassion in general and compassion for animals in particular can be reflected in using phrases such as ‘We take milk from cows’ rather than ‘Cows give us milk’ or ‘Amundsen was the first to reach the South Pole’, rather than ‘Amundsen conquered the South Pole.’

c. Discipline Principle: Textbook developers should have sound knowledge of the discipline associated with the textbook being developed. The content and sequence included in the textbook should be carefully selected so as to not contradict some of the core principles of these disciplines.

d. Pedagogy Principle: Textbook developers need to have a clear understanding of the pedagogy that is appropriate for the Competency and content (e.g., in Language, the balanced approach of including oral language, phonics and word-solving instruction, and meaning making needs to be incorporated all together for the Foundational Stage). They should also strive to keep textual matter to a careful minimum, avoiding the earlier common practice of overloading textbooks with details of questionable significance.

e. Language Principle: The language used in the content of the textbooks should be fully cognizant of the Language Competencies expected for that particular grade in the Learning Standards. Particularly in the early grades (Foundational and Preparatory Stages), students are still learning to read and textbook developers of all subjects must take this into consideration. Unfamiliar vocabulary and sentence structures should be appropriately scaffolded in the textbooks through glossaries and explanations. In higher grades (Middle Stage onwards), developing academic linguistic proficiency should not be seen as the responsibility of only language textbooks. Subject textbooks should highlight language use specific to that subject.

f. Technology Principle: Textbook developers should be aware of the current technology and audio-visual materials available for enhancing the learning experiences of students. Activities that involve digital technology and references to external material should be embedded appropriately in the textbook.

g. Context Principle: The local context and environment are important considerations for the choice of content in textbooks for the Foundational and Preparatory Stages. Moving from the familiar to the unfamiliar is an important aspect of learning. The textbook should also contain a balance of familiar contexts that is a comfort for the students and unfamiliar contexts that should generate curiosity and challenge their thoughts and preferences. For the Middle and Secondary Stages, this may not be a strong consideration in all Curricular Areas.

h. Presentation Principle: The textbooks should be so well designed that they grab the attention of students. For the Foundational and Preparatory Stages, the balance between visual material and text should be tilted towards visual materials. The colour schemes and design themes should be attractive and consistent. The fonts and size of text material should be visible and least confusing for young children to decode. For the Middle and Secondary Stages, attention should be given to the flow of concepts, clarity in articulation, and the design of illustrations, not only to clearly illustrate the concepts, but also to initiate discussions and invite students to ask questions.

i. Diversity and Inclusion: It is important to maintain the principles of diversity and inclusion in the choice of content for textbooks. Even within States, there are regional variations and these need to find adequate representation in textbooks.

3.2.2.3 Important Elements in Textbooks

Important elements that textbook developers need to keep in mind are:

a. Design aesthetics and Consistency: The look and feel of textbooks are nearly as important as the content presented in the textbooks. Design aesthetics and consistency across textbooks make it easier for the students to engage with textbooks.

b. Learning Standards: Chapters in all textbooks should be explicit and clear about the intended Learning Outcomes of the content presented in the chapter.

c. Consistent Design Elements: Each Curricular Area would have specific elements that consistently occur in each chapter of a textbook. These elements are particular to the Curricular Area and Stage. For example, language textbooks in the Foundational Stage can have elements, such as Oral Language, Read Alouds, Phonics and Word Solving, Comprehension, Writing, and so on. A common design theme that clearly identifies and distinguishes these elements would make textbook design clear and the expectations explicit.

d. Activities and Exercises: Exercises need not be only at the ends of chapters. Appropriate activities and exercises can be embedded in the flow of content in the textbook. Exercises should reflect a judicious mix of recall as well as exploratory and higher order thinking tasks. Recommended activities that have clear instructions and expectations allow for engagement outside the classroom. Where appropriate, recommendations for homework should also be included as part of activities and exercises.

e. Reference to Additional Materials: It has to be emphasised that textbooks are not the only source of content. Along with this, it has to be acknowledged that, while the internet offers almost limitless access to content and knowledge, often the sheer choice is bewildering and confusing for a young learner. Textbook writers should also play the role of curators and provide references to additional materials available freely on the internet through QR codes, provided that they have verified the genuineness and relevance of such materials. This should be a standard feature of every chapter in the textbook.

3.2.2.4 Process for Textbook Development

Applying the principles of textbook development, the process could be the following:

a. Creation of a syllabus document that draws from the Curricular Goals, Competencies, and Learning Outcomes and the nature, pedagogy, and assessment of a subject. The syllabus document could include the objectives of teaching the subject, approach to the content to be included (concept or theme), structure of the syllabus document (as questions, key concepts, suggested strategies or activities), and choosing content that is cognitively and socio-culturally relevant. The syllabus document could also use literature from research studies, policy papers, Teacher experiences, and subject matter expert opinions for deciding the extent and depth of the content.

b. Panel of textbook writers, reviewers, and designers/illustrators — The people involved in textbook development could be:

i. Textbook writers and reviewers. Teachers must be part of this group; others could include subject experts and university faculty and research scholars. Textbook authors should include people from diverse backgrounds to bring in diverse perspectives for content.

ii. Designers/Illustrators. People/organisations that have design experience and understanding of the local context, preferably local experts, should be involved from the start of the process.

iii. Technical Experts. A lot of content that complements the textbook can be made available through digital media. It is thus important for technical experts to be part of the textbook development team from the start — media content should not be an afterthought.

The group should work together from the beginning to develop a shared vision of the textbook and create a common understanding of the process and be open to feedback, suggestions, and multiple iterations of the textbook.

c. Choice of content, pedagogy, and assessment. The topics/themes chosen would need to include the context of the student (including previous experiences and language) and scope for further exploration. The content for each Grade should be a precursor to the next. It is essential to ensure an alignment of the pedagogy and assessment with the content and the Learning Outcomes.

d. Structure of the textbook. Considering that the textbook is one important source of connection between the Teacher and the student, the textbook should be useful for both. Content in textbooks is largely directed towards students. It has been a practice to include notes for Teachers in the textbook. This approach is limiting. Therefore, this NCF recommends that each textbook released for students should be accompanied by a Teacher’s version of the same textbook. (Please see Box 3.2i below)

e. Presentation and Design. The presentation of a textbook relies on the font size, images, sketches, the colours used, and their amalgamation, e.g., textual content in the early Grades may be limited with a large number of images, font size should be large, and the illustrations used should be sensitive and inclusive. The language used should be Grade appropriate and relevant to the subject.

f. Writing, review, and pilot run — The writing of a textbook needs sufficient time, regular peer reviews, and panel reviews. It requires regular interactions with the illustrators to define and reiterate the requirement of the content being worked on. This adds to the rigour of textbook creation and assists in avoiding repetitions in the text, images, and ideas across subjects as the illustrators work with all the writers.

The reviews provided should be constructive and encouraging. The feedback should include suggestions and alternative ideas. The writers should be open to multiple iterations and be cognizant of the principles of writing content. The review process must be done chapter wise and then for the textbook as a whole. Meticulous proofreading of the textbook is essential and contributes to its quality.

Selected schools must be identified pilot runs of the textbooks. During such a pilot run, the writers must visit schools and schedule classroom observations, conversations with Teachers, student, and parents and receive feedback about the textbook.

g. Teacher orientation to the textbook. There must be a provision for Teacher orientation on the genesis of the textbook, its rationale, and the approach to pedagogy and assessment to ensure its appropriate use in the classroom. This orientation must be followed up through school visits, webinars, sharing of best practices, and regular interactions with the Teachers to understand the challenges being faced in the use of the textbook.

h. Multiple textbooks: Many agencies and teams must be encouraged to develop textbooks based on the same syllabus.

Teacher’s Handbook It has been a practice to include notes to Teachers in the textbook. This approach is limiting. If notes are kept to their briefest minimum, it is not really useful for the Teacher. If they are elaborate and detailed, it unnecessarily increases the size of the textbook for the students and it perhaps would also be intimidating. It is recommended that each textbook being published be accompanied by a Teacher’s version (Textbook+) of the same textbook. The Textbook+ should be organised in the same sequence of chapters as the students’ textbook, but can include additional materials: • Intended learning objectives of the chapter and how it is connected to the Learning Standards of the curriculum. • Recommended pedagogical strategies relevant for that chapter. • Alternative activities for students who are struggling to grasp the content. • References (through QR-Codes) for resources, such as digital materials, additional worksheets, formative assessments, and pedagogical content knowledge packages that provide additional teaching aids and also develops a more profound understanding in the Teacher of the topic under consideration. Thus, the Textbook+ would be a valuable compendium for the Teacher to go well beyond the textbook’s content without burdening or intimidating the students.

3.2.3 Learning Environment and Teaching-Learning Materials

A safe, inclusive, and stimulating environment that supports every student’s participation is critical for achieving the Learning Standards outlined in the NCF.

Classrooms (and schools overall) that are clean, well-ventilated, well-lit, and organised with appropriate access and safety provisions are important to facilitate learning. Safety provisions include physical, social, and emotional safety.

Schools must be equipped with adequate resources and materials. Classrooms should allow for individual work and cooperative work. Classroom displays should be available for student work. Students with developmental delays or disabilities may need specific accommodations for physical space and TLMs to enable physical and curricular access.

For the Foundational and Preparatory Stages, classrooms may be organised into Learning Corners for specific domains of learning. The availability of a range of safe and stimulating material that encourages learning in different domains of development, literacy, and numeracy would be necessary for all students.

Well-resourced libraries and laboratories would be necessary for the Middle and Secondary Stages. Art Education, Physical Education and Well-being, and Vocational Education would require specific kinds of spaces and materials available and organised in particular ways.

The local context and the resources of the community may also be significantly helpful, when used and integrated thoughtfully.

It is important that the full potential of the environment and various kinds of TLMs are utilised, all of which is intimately tied to the approach adopted in pedagogy (elaborated upon in the next section). Not only would this enable aspects of learning that are difficult to foster only through books, but it also makes the process more engaging.

Thus, the curriculum content selected (including pedagogical aspects) must be carefully distributed and balanced between books, other TLMs, and the use of the surrounding environment.

Section 3.3 - Pedagogy

NEP 2020 states:

- A good educational institution is one in which every student feels welcomed and cared for, where a safe and stimulating learning environment exists, where a wide range of learning experiences are offered, and where good physical infrastructure and appropriate resources conducive to learning are available to all students.

[NEP 2020, Principles] *

Pedagogy is the method and practice of teaching used in classrooms by the Teacher to help students learn. Effective pedagogy is based on a good understanding of how children grow and learn, and a clear focus on Curricular Goals, Competencies, and Learning Outcomes to be achieved for students.

3.3.1 How do Children Grow and Learn?

Healthy physical development requires basic needs of adequate nutrition and appropriate sensory and emotional stimulation. There are ‘critical periods’ in sensory development, e.g., normal visual experience is critical within the first few months of life. There are ‘sensitive periods’ in cognitive and emotional development as well, e.g., early childhood and adolescence. Physiological changes have ramifications on the psychological and social aspects of a child’s life. From an evolutionary point of view, human beings are born to learn, so we come with a drive to understand the world and explain things around us. We constantly make our own theories and refine them based on our perceptions and experiences.

Children are, therefore, natural learners. They are active, eager to learn, and respond with interest to new things. They have an innate sense of curiosity — they wonder, question, explore, try out, and discover to make sense of the world. By acting on their curiosity, they continue to discover and learn more.

Research from across the world has provided us with a set of ideas about how children learn that have practical implications for teaching. Some of these key aspects are:

a. The brain plays an important role in learning. The brain is a complex organ made up of neurons, glial cells, blood vessels, and many, many cells organised into specialised areas. The working of the brain is the ever-changing patterns of connections between millions of neurons. Learning is a physical process in which new knowledge is represented by new brain cell connections. The brain both shapes and is shaped by experience, including opportunities the child has for cognitive development and social interaction. The brain is designed to learn and remember new things through life, as long as it continues to be challenged and stimulated.

b. Learning is based on the associations and connections that children make. Children are far from blank slates on which we can simply write pages and pages of information. They have knowledge and understandings based on their experience; they have intuitive theories about varied subjects. Nothing is ever recorded in a child’s brain exactly as it is experienced. It is their interpretation of what they experience that becomes new knowledge. Interpretation is always in the light of whatever knowledge they already possess. Children are continuously fitting new experiences into existing knowledge and adjusting existing knowledge to allow new experiences.

c. Emotions are deeply connected to learning. Emotions are inextricably intertwined with attention, motivation, and cognition. Positive emotions, such as curiosity, wonder, joy, and excitement aid attention, cognition, and memory and, therefore, learning. Positive emotions are often best nurtured through positive relationships with Teachers and among students. When students feel they belong in a classroom and they can trust their Teacher and classmates, they feel free to try out and explore and learn better in the process. As trust grows, the classroom becomes emotionally safer, and students have fewer obstacles to building their confidence and their learning.

d. The learning environment matters: The word ‘environment’ refers to both the physical space and the ‘atmosphere’ or psychological environment in the classroom. The physical environment provides a structure that allows safe exploration, cognitive growth, and challenge. The atmosphere or psychological environment is made up of all the relationships and social interactions that happen in the classroom. A safe, secure, comfortable, and happy classroom environment can help children learn better and achieve more. For this, it is important that the necessary facilities, such as learning materials, aids, equipment, and space for doing activities, working together, and playing so as to help each child learn better, are made available. The classroom must be an inclusive, enabling learning environment that provides every child with respect, openness, acceptance, meaningfulness, belonging, and challenge.

e. Learning occurs in particular social and cultural environments: Learning in school becomes meaningful when it connects to students’ lives and experiences. Most children grow up with stories, songs, games, food, rituals, and festivals special to their families and community along with local ways of dressing or working or travelling or living that are an integral part of their everyday lives. The diverse experiences of children must find a place in the classroom. As children grow up, while there may often be a difference between the culture of a student’s home and the culture of the classroom, it is important to continue to listen to student’s voices and honour their cultural traditions in the classroom.

3.3.2 Effective Pedagogy for Achieving Aims of School Education

As stated in Chapter 1, §1.3, the central purpose of schools as formal educational institutions is the achievement of valuable knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions by students. Based on how children learn, some key elements of pedagogy for achieving these aims are described below.

a. Knowledge (knowing that — concepts, theories, principles) Children form concepts and intuitive theories right from infancy. To learn a new theory or concept or principle, students fit this new experience into their existing knowledge and adjust their existing knowledge to allow new experiences in. To help students do this well, Teachers need to structure and sequence the teaching of concepts appropriately. They need to connect new concepts to students’ existing experiences and understanding, pose questions that challenge their existing understanding, and make clear demonstrations that push their thinking beyond their existing understanding. All this should take place while ensuring their full participation in open discussions and hands-on activities. Teaching concepts, theories, or principles in disconnected chunks or expecting students to reproduce them in the same way they were received makes true conceptual understanding impossible.

Importance of Memory The ancient Indian emphasis on smriti (memory) is critical to learning and development. It has often been misunderstood as an emphasis on rote learning, which in principle and when practised with fidelity, it is not. Current cognitive science research indicates that smriti (memory) — both working memory and long-term memory — plays an important role in cognition and comprehension. Insufficient emphasis on memory often results in inadequate outcomes in the classroom. When we use memory inappropriately, we are ignoring its powers and capacities. Using memory for learning in the classroom encompasses a variety of activities — deliberate and regular practice, deep processing, generating cues, making connections, and forming associations.

b. Capacities (knowing how — abilities and skills)

Abilities and skills are learnt best by doing and they improve with repeated exposure and practice. Good practice involves meaningful variety must be done in appropriate quantity and is supplemented with continuous discussions on why certain procedures work and others do not.

Importance of Practice *Learning is a time-consuming process. Organised, regular, and steady practice yields steady and positive impact on learning. Practising helps to internalise information, access more complex information stored in long-term memory, and apply knowledge or skills automatically. Across Curricular Areas, differences in students’ performances are affected by how much they engage in deliberate practice. Deliberate practice is not the same as rote repetition. Rote repetition does not improve performance by itself. Deliberate practice involves attention, rehearsal, and repetition and leads to new knowledge or skills that can later be developed into more complex knowledge and skills. When a skill becomes automatic, attention and mental resources can be freed up for higher level thinking and reasoning. Most Teachers are aware of two contradictory facts — drill can be boring, and yet practice is the only way for their students to master certain procedures. The problem with drill comes when we assume that it will substitute for understanding. Concepts and procedures are two different things, both of which students need to learn. Practice alone cannot lead to conceptual knowledge; understanding alone cannot lead to mastery of a procedure. *

c. Values and Dispositions

‘Telling’ students about what values they should develop or uphold usually has little effect. It either becomes ‘boring’ or is perceived as ‘preaching.’ Development of values and dispositions in school education happens primarily in the following ways:

i. Through school and classroom culture: Sensitivity and respect for others is encouraged when opportunities are provided for all students to participate in activities and select students do not end up participating in all activities. Students also learn from seeing exemplars.

ii. Through school and classroom practices: Seeing exemplars, listening to/reading stories about particular values, or participating in bal sabhas and bal Panchayats that help build notions of democracy, justice, and equality.

iii. As part of learning through school subjects: Laboratory experiments and trials help build scientific temper and thinking.

iv. As direct goals of some school subjects: Learning to win and lose with grace during sports and games helps build resilience.

Importance of Questioning There has existed a long and ancient tradition of questioning in India. Debate and discussion have always been held as a critical part of the Indian knowledge tradition. The Upanishads were written in response to the questions of shishyas. The literal meaning of the word Upanishad is the sitting down (of the shishya) near (the guru). The usual method of argument utilised reason and went from simple to complex, from concrete to abstract, and from known to unknown. In the Katha Upanishad, is the powerful story of Nachiketa, a young boy, who dared to ask Yama, the lord of death, a very simple but fundamental question: ‘Is there life after death, or is death the end?’ The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad narrates the debate of Yajnavalkya with Janaka and Gargi about the nature of the Self. In the Chhandogya Upanishad, Uddalaka Aruni debates with his son Shvetaketu on the nature of the ultimate reality. The Mahabharata’s Yakshaprashna has the famous dialogue between Yudhishthira and his own father, Dharma. At different points in Indian history, there have been extraordinary scholars who were outstanding masters in their respective schools of thought. It was very common among learned people to debate the worth and limitations of these various systems of philosophy publically. The legendary debates between Adi Shankara and Mandana Misra are a good example. Hordes of scholars often came from afar every day to watch and learn from them. These debates between two exceptional masters show how healthy competition existed so routinely among followers of different philosophies. Many such learned masters demonstrated open mindedness and the willingness to test their faith, beliefs, and philosophies, and if the reason arose, even changed their beliefs and the contours of the philosophies. Innumerable Indian scholars had to be accepting towards new concepts, experiments, or questionings in this way Countless popular stories, such as those of King Vikram and Vetal, of Birbal and Akbar, of Tenali Raman, also bear testimony to scholars debating and challenging each other through riddles, intellectual games, or profound philosophical questions using simple everyday language.

Some values are developed better through particular processes; illustratively,

a. Regular dialogue and discussion with active listening as part of classroom culture and processes will help develop democratic values (e.g., pluralism, equality, justice, fraternity) and appreciation of others’ viewpoints.

b. Curricular Areas such as Art Education and Physical Education and Well-being will help build individual virtues (e.g., honesty, courage, perseverance, teamwork, empathy, respect for others).

c. Curricular Areas such as Science and Mathematics will help build epistemic values (e.g., scientific temper, rigour in reasoning).

d. Marking important days through community service as part of school culture and practices will help build cultural values (e.g., nishkama karma, seva, ahimsa, shanti) and respect for and tidy reinforces the importance of swacchata. Practicing reducing, recycling, and other green practices in schools encourages harmony with the environment and sustainable lifestyles.

e. Regular practices at the school assembly will help promote pride in India’s cultural unity and diversity.

3.3.3 Key Elements that Enable Effective Pedagogy in the Classroom

a. Ensuring respect and care.

Our schools are committed to providing an environment where children feel secure, and relationships are governed by care, equity, and respect. Any form of discrimination based on religion, caste, gender, community, beliefs, disability, or any other factor is unacceptable. Teachers must value and respect all students. Classrooms should be spaces that will offer all students equal access and opportunity to achieve learning outcomes. All students will participate in a variety of activities and school processes, not just those with the best chances of success. Our schools will create an environment that enhances the potential and interests of each student.

Care is central to learning in schools. Care is an attitude of concern and responsibility for people and relationships. Empathy and respect are at the heart of caring.

b. Building positive Teacher-student relationships.

A safe, positive relationship between Teacher and student is enriching both for cognitive and socio-emotional development.

Some important ways to build such a positive relationship are:

i. Getting to know each student individually — this helps understand and plan individualised learning experiences for each student

ii. Listening carefully to students — this conveys care and respect, builds trust, and helps students gain confidence

iii. Observing students — this helps discover how each student thinks, reasons, and responds to different situations, which is critical to planning for teaching and learning

iv. Encouraging student responses — this helps meaningfully build on student’s naturally creative and resourceful selves

v. Encouraging questioning — questions to and from the Teacher help students think through a particular subject in depth while responding.

vi. Recognising and responding to the emotions and moods of students — this helps them settle and learn better, learn to regulate their own emotions, and understand and respond to the emotions of others.

vii. Responding gently — if a student behaves inappropriately, the Teacher should have a range of strategies to handle it, starting with gentle, compassionate one-to-one interaction to understand what might cause such behaviour. Most students respond much better to such strategies than to scolding or punishment.

Ways of the Guru According to Sri Aurobindo, the three instruments of the Guru are teaching, example, and influence. Wise Teachers do not seek to impose themselves or their opinions on the passive acceptance of receptive minds. They seek to awaken much more than to instruct, and they aim for the growth of faculties and experiences by a natural process and free expansion. They prescribe a method as an aid, as a utilisable device, and not as an imperative formula or a fixed routine. As the Taittiriya Upanishad tells us, the Teacher is the first letter, the student is the last letter, knowledge is the meeting place, and instruction is the link.

c. Providing scaffolding.

Students can easily learn new knowledge when systematic support from other experienced students or adults is provided. Learning new knowledge should be a challenge, but the challenge should be within the reach of students — something that relates to their existing knowledge and can be done with the support of an experienced person.

Scaffolding refers to providing support, structure, and guidance during instruction. Scaffolding differs depending on the task but occurs when the Teacher carefully assigns students a learning task and provides support along the way until gradually fading as the student reaches expertise.

One way of scaffolding is through a ‘Gradual Release of Responsibility’ (GRR), where first, Teachers model or explain ideas or skills, after which students and Teachers work together on the same ideas and skills where the Teacher provides guided support. Finally, students practise individually and independently.

d. Using differentiated instruction.

Teachers will need to plan classes in a way that engages students with varying interests and capabilities meaningfully and encourages better learning.

One way to think about this is differentiated instruction, i.e., tailoring the teaching process according to the individual needs of students. Content, methods of learning, material, and assessment may be different for different students. It is often difficult to do this for individual students, especially in a large class. In that case, the Teacher could identify small groups of students who have similar needs and address them differently as a group.

Before planning for this, it is important for the Teacher to observe students carefully, analyse their work, and gather as much information as possible about them. For example, the Teacher could plan to use worksheets of varying levels, starting with simple worksheets and progress to more complex ones according to what different groups of students in the class are able to do.

e. Providing opportunities for independent and collaborative work.

Classroom processes should provide opportunities for students to work individually and to work together. Teachers may ensure that students work in pairs, in small and large groups, as well as independently. Teachers must help students listen, understand, appreciate, and reflect on their own thought process and other’s experiences with empathy and critical understanding. Working with others often increases involvement in learning. Sharing one’s own ideas and responding to others’ reactions improves thinking, deepens understanding, and also leads to new insights and ideas. In carefully crafted collaborative learning situations, students require each other’s contributions to successfully complete a learning task because of which they need to learn to take on varied roles, such as observers, mediators, score managers, and note-takers based on the objectives of the task.

f. Using varied resources.

Using the textbook meaningfully is important for learning. In addition, other resources and materials must be used to engage students beyond the textbook. Classroom processes should incorporate use of resources made by students, Teachers, and the local community, as well as those available in the immediate environment. Digital resources must also be incorporated appropriately.

Classroom displays constitute an important part of the learning process which does not have to be limited to finished products alone — they could also include aspects of work in progress. Where possible, classroom displays should be dynamic, updated regularly, and aim to be aligned to the topics and questions students are engaging with. Permanent displays should be kept to a minimum.

*g. Helping students develop appropriate work habits and responsibility. *

Developing appropriate work habits and taking responsibility are critical to learning. These include aspects such as students’ organising space and materials before and after use, organising time, ensuring time on tasks, taking responsibility for tasks, persisting with and completing work, staying on a given task even without a Teacher present, and allowing others to work without disturbance.

h. Giving prompt and meaningful feedback.

Students need immediate and appropriate feedback to benefit from classroom processes and improve their learning. Integration of suitable technology can also be considered to support students with disabilities. Feedback helps students reflect on what they have learnt and what they still need to know.

Providing feedback means giving students an explanation of what they are doing correctly and incorrectly, with the focus of the feedback on what the student is doing right. Waiting too long to give feedback might make it difficult for the student to connect the feedback with the learning moment. It is vital that we take into consideration each individual when giving student feedback. Some students need to be nudged to achieve at a higher level and others need to be handled gently so as not to discourage their learning and damage self-esteem.

3.3.4 Planning for Teaching

Teaching is a deliberate act carried out with the intention of bringing about learning in students. This deliberate act needs to be well planned. Planning is central to good teaching. Planning includes construction and organisation of classroom tasks as per Competencies and Learning Outcomes to be achieved, pedagogy to be followed, resources to be used, and assessment to be carried out. Planning also includes support activities for students, home assignments, and displays in the class relevant to what is being taught.

Good planning requires understanding of Aims of Education, Curricular Goals, Competencies, and Learning Outcomes to be achieved, along with prior learning of the students for whom the plan is being made and available TLMs and content to be used.

The major components of a teaching plan are:

a. Competencies, Learning Outcomes, and intended lesson objectives

b. Teacher-directed, Teacher-guided, and/or student-led activities to achieve objectives

c. Prior understanding of the student on which choice of pedagogy is based

d. Content and material to be used

e. Duration and sequence of activities

f. Classroom arrangements (e.g., seating, displays, arrangement of material)

g. Specific strategies for students who need extra help

h. Methods of assessment

*

Panchpadi — Five-Step Learning Process The five-step learning process — panchpadi — is a good guide to formulating the sequence that a Teacher may adopt in planning for instruction for certain concepts and contexts: Aditi (Introduction): As a first step, the Teacher introduces a new concept/topic by establishing a connection with the child’s prior knowledge. Children gather relevant information regarding the new topic with the help of the Teacher by asking questions, exploring, and experimenting with ideas and material. Bodh (Conceptual Understanding): Children try to understand core concepts through play, inquiry, experiment, discussion, or reading in the second step. The Teacher observes the process and guides the children. The teaching plan has the list of concepts to be learnt by the children. Abhyas (Practice): The third step is about practice to strengthen understanding and skills through a range of interesting activities. Teachers can organise group work or small projects to reinforce conceptual understanding and attainment of Competencies. Prayog (Application): The fourth step is about applying the acquired understanding in the child’s everyday life. This can be accomplished through various activities and small projects. Prasar (Expansion): The fifth step is about spreading the acquired understanding (pravachan) and using other resources to learn further (swadhyay). Pravachan is largely mediated through peer learning — conversations with friends, telling each other new stories, singing new songs, reading new books together, and playing new games with each other. Swadhyay is mediated through engaging with materials and experiences related to learning. For each and every new topic learnt, a neural pathway is created in our brain. Sharing and enhancing knowledge strengthens our learning. A neural pathway is incomplete if we do not teach what we have learnt. Teaching makes learning clear and long-lasting.*

3.3.5 Managing Classrooms/Student Behaviour

Students behave inappropriately for many reasons. Behaviour is often the unspoken language through which young students act out feelings and thoughts. Sometimes, they use behaviour to seek extra attention. Adolescents could be angry or helpless and do not know any other way to express these feelings. Sometimes, this behaviour could be because of lack of sleep, poor nutrition, health issues, developmental delays or deficits, or even family dysfunctionality or stress. Norms, rules, and conventions must enable students’ learning. Evolving clear classroom norms that can be implemented would help everyone own them rather than have a classroom function on the basis of fear.

Instances of indiscipline must be seen through the lens of development, with a balance of humour and compassion, and with careful intervention that is firm yet kind. These should be used as learning opportunities in helping students to solve problems.

Discipline must be seen from the lens of self-regulation and self-discipline and as a necessary condition for development and the pursuit of learning. It is important for students to take responsibility for their behaviour and face appropriate consequences as they grow older. Adults bear greater responsibility than students in creating an environment of respect and equality. Illustratively, school staff is expected to intervene if they see students using physical violence, bullying each other, or being unkind/unfair to each other, and must put a stop to it immediately and firmly. They must encourage students to settle differences of opinion through dialogue and communication.

Importance of Concentration The Taittiriya Upanishad says that the secret of learning lies in the power of concentration in thought. The science of Yoga is based on the process of concentration and the methods by which concentration can be achieved on the object of knowledge so that the contents, powers, and states of knowledge concerning that object can be realised by the seeker. Sri Aurobindo also lays central importance on concentration and speaks of four principal methods by which concentration can be attained: meditation, contemplation, witnessing the passage of thoughts as they pass through the mind, and quieting and silencing the mind. Concentration is a psychological process — it involves no rituals or ceremonies and is free from any doctrines. Hence, the cultivation of the powers of concentration is independent of any activity necessitating faith, belief, or religious prescription.

3.3.6 Responding to Students with Disability or other Individual Learning Needs

Classroom processes should respond to the diverse needs of students. Students learn best when they are challenged, but not so much that they feel threatened or overwhelmed by the level of challenge. Therefore, Teachers would need to know and understand the learning needs of every student in their class and provide the appropriate level of challenge and support to each student. During the normal course of teaching, based on routine observations and assessments, Teachers could identify those students that may require additional support or individualised attention. This in no way should lead to labelling of students as ‘bright,’ ’slow,’ or ‘problem’ students, nor does it imply ‘lowering’ of standards.

Some of the ways in which this additional support could be provided or students could be offered varying levels of challenge are listed below.

a. A ‘bridge’ course for a month or so at the beginning of the year, which will enable students to refresh their previously learnt concepts and prepare for the new class.

b. Specific work on designated days to supplement what has been done in class.

c. Differentiated assignments — the Teacher could provide assignments/class tests of varying levels of difficulty using the same content.

d. Making specific resources available to students who need them, such as extra worksheets for those who need additional practice and ‘extra-challenging’ worksheets for those who might enjoy or benefit from it.

e. Set up a ‘buddy system’ wherever appropriate — pair a student who needs help with another student who can provide it informally, e.g., to help with homework, offer explanations after class, or carry out projects together.

f. Setting up a conference time once a month or so with every student in class so that the Teacher has a chance to communicate one-on-one with every student and identify conceptual problems, learning difficulties, or individual needs of all students.

g. Communicate regularly with all parents, but particularly those parents whose students may need special help and support so that parents are also able to provide support when required. The nature of this communication needs to be specific and clear to parents so that they know and understand what needs to be done to help their child.

h. In cases where the school is not equipped to help or support a student with an identified disability adequately, it may rely on external resources or resource persons. Integration of suitable technology can also be considered to support students with disabilities. Schools will understand and opt for all exemptions provided by Boards of Education in specific situations. All such decisions should be made in partnership with families.

3.3.7 Homework

Homework is an extension of the learning process. Work done at home is a consolidation of work done in school and helps make students capable of doing things on their own. It is based on the teaching provided to them in class. At the same time, homework should not be intended to merely repeat what has been learnt in class, but rather to apply it to different contexts.

Homework tasks must therefore be meaningful for learning. It may include practice work (e.g., worksheets to be completed) as well as application of concepts through specific tasks (e.g., survey of local water resources).

Tasks and allocation of time spent on homework must be age appropriate. Teachers must also ensure that students can do these tasks on their own and they do not require parents or others to do anything on their behalf.

Homework can be fun and provides a different kind of interesting challenge to students. It can also help to connect school with the student’s home, especially in the Foundational and Preparatory Stages.

3.3.8 Pedagogy across Stages

An effective approach to pedagogy in a particular School Stage is based on how children grow and learn (i.e., physical, cognitive, socio-emotional, language, and moral development) and the overall aims of education to be attained in that Stage. Such an approach will help achieve Curricular Goals, Competencies, and Learning Outcomes without compromising the holistic and expansive notion of individual development that NEP 2020 focusses on.

As stated earlier in this document, while the Stages are distinct, students’ growth and maturation are part of a gradual transition with overlaps and commonalities, especially across two adjacent Stages (e.g., teaching for sensorial and perceptual ways of learning in the Foundational and Preparatory Stages, and teaching independent learning habits and discerning use of media gadgets in the Middle and Secondary Stages). It can also be seen that some changes occur in a continued fashion over the same facets within physical, emotional, social and ethical, and cognitive development over the Stages (e.g., changes in physical strength and flexibility, in expressed need for emotional support, in the need for conformity and peer approval, and in abstract thinking and independent reasoning abilities).

a. Pedagogical considerations related to physical development.

i. Foundational Stage: Early years of school are formative and crucial in paving a positive experience of the learning environment. Any teaching strategy in this Stage that speaks to vibrant energies, enables playful interactions, engages in enjoyable stories, uses curious toys, and allows for full-body engagement with learning would be ideal and effective. Children continuously engage through their senses and make the most of the world around them this way. Pedagogy that encourages them to engage physically in aesthetic experiences of music, dance, art, and crafts makes for an enjoyable school day. Teaching about health and hygiene practices ensures physical well-being in the long term.

ii. *Preparatory Stage: *Students continue to be physically active, highly perceptual, and engage with hands-on activities and make sense of concepts with the help of concrete physical learning aids. This requires Teachers to demonstrate energetic and active participation in the things the students are required to do as part of their learning. The Teacher needs to teach through modelling how to make sense of concepts more perceptually and practically with low levels of verbal complexity and theorising. The content that is chosen, the teaching plan, assessment, and classroom arrangement would need to be activity-based, playfully experimental, and lend themselves to a conversation and consolidation after ‘doing.’

iii. Middle Stage: This is a Stage of gradual and sudden changes in physical development. With adolescence and prepubescence on the cards, Teachers will need to be prepared for handling growth pains and growth spurts with changes in strength and increased restlessness in their students. A good understanding of gender and sexuality would also help Teachers understand their students better. Understanding families and local culture will help with understanding student behaviour in school. It is also a time when students must be encouraged to independently practise their learning despite the resistance that might come up.

iv. Secondary Stage: At this Stage, students grapple with their changing bodies, may become self-conscious, and may be trying to make sense of their maturation. Pedagogy across subjects must accommodate for changes in students’ perceptions of their bodies and abilities, provide adequately challenging physical tasks, and encourage greater participation in both group and individual activities, especially sports and games.

b. Pedagogical considerations related to emotional development.

i. Foundational Stage: Children would require Teachers to help them learn about understanding their own emotions and the emotions of others. The context of a school allows for a safe space for such conversation and learning. Learning to regulate feelings and behaviour, delaying the need for instant gratification, and practising positive learning habits will go a long way in the lives of children so these aspects must be facilitated and encouraged actively and regularly. Children will require close individualised attention and care.

ii. Preparatory Stage: Students at this Stage are also rapidly learning to make sense of their thoughts and feelings and would need guidance with learning emotional regulation. Many of them would already display temperaments and preferences and Teachers will need to engage and tease out emotional habits coming in the way of learning through their teaching interactions. They will also need to provide alternative possibilities to the emotional experiences of the students. Gradually, students must be supported and encouraged to become emotionally independent.

iii. Middle Stage: The classroom and the school as a site for emotional learning, growth, and expression are probably the most occupying for Teachers at this Stage. Students themselves go through unpredictable mood and energy fluctuations, often grappling with a sense of unexplainable wellness or not-so-wellness. Middle Stage pedagogy must allow for some amount of engagement with emotional experiences through quiet discussion and reflection. Curricular Areas can be used as contexts in which individual responses can be parsed. The Teacher will have to find a balance in the approach to students’ emotions — an approach that is neither intrusive nor indulgent, but reasonably firm, rationally clear, and emotionally caring towards students of this Stage.

iv. Secondary Stage: It would be necessary for pedagogic strategies to guide individual reflection and group conversation on thoughts and feelings that emerge through engaging with curricular components. A philosophical understanding that feelings are transient and not set in stone, that individuals can act upon their emotions in healthy and unhealthy ways, and the social consequences of rational versus irrational decision-making based on emotional reactions are good discussions to have at this Stage. The focus on emotional regulation must continue. Teachers will have to be discerning about when students require one-on-one attention and find ways to communicate with them effectively.

c. Pedagogical considerations related to social and ethical development.

i. Foundational Stage: Teaching students social norms and strategies to adhere to, teaching valuable social participation and contribution in accomplishing simple tasks, and teaching the meaning of cooperation and respect for others are all immensely important in social and ethical development at the Foundational Stage. Social life is a long-lasting reality that children must learn to intelligently navigate early on. Ethical and moral instructions at this Stage are aimed at teaching children simply the ‘good’ and appropriate from the ‘bad’ and inappropriate actions.

ii. Preparatory Stage: This Stage is also a time for learning about social participation and contribution. The pedagogic strategies must enable pair work, small group work, and individual work in mixed proportions so that students are actively learning to work together with sensitivity, mutual respect and listening, cooperate with others, and also accept cultural differences and diversity of approaches in thinking and feeling. Teachers must engage students with basic ethical and moral questions about equality, fairness, sharing, and cooperation.

iii. Middle Stage: Peers seem to become far more prominent in the lives of students at this point and this can be leveraged to the advantage of the learning atmosphere. Like the Preparatory Stage, the pedagogic strategies here too must plan for pair work, small group work, and individual work in good proportions. Mixed small group work would allow for listening to and thinking together with different people. Many lessons must allow for learning to work together with others, for healthy ways of testing one’s abilities through social facilitation, and for respectful and sportive competition. The pedagogy must explicitly aim (through content selection and interactional strategies) at fostering sensitivity and respect for diversity in gender, class, and cultural background. Students will need to learn to navigate their social world (including parents, Teachers, and community) and will require clear expectations and rules set in these interactions. Teachers could discuss equity and respect for others as part of ethical reflection in class. It is also a time when they start learning about the world as much bigger than their immediate surroundings, so it is important to give them a sense of the cultural diversity that they are part of in our historically, geographically, and culturally rich country.

iv. Secondary Stage: Students at this Stage are young people with emerging opinions and loyal allegiances and with capacities for energetic participation and vehement dissent. Forming strong allegiances, explicit interest in varied ideologies that one can identify with, idealising individuals (from politics or sport or the entertainment industry) and other similar impulses seem to show up in this age group based on the need for belongingness in students. Actual friendships, tightly knit small groups (ingroups and outgroups), and peer conformity would be features that can be used to the advantage of learning about oneself and the world around them. This is also the time to actively encourage individuation in thinking and reasoning while being able to respectfully listen to and understand others. Challenges, such as bullying, isolation, and confusion, with boundaries will need to be met in the context of the classroom and outside.

Teaching strategies can include delegating responsibilities, allowing students to take charge of their own learning, and regulating each other’s learning with a focus on helping others learn better. Teachers could actively talk with students about ethical and moral actions connected to social participation and change. It is also an important time in the lives of students to address ideas of identity and heritage about what it means to be Indian (Bharatiyata) and belong to our vast and culturally rich nation.

d. Pedagogical considerations related to Cognitive development.

i. Foundational Stage: Pedagogic strategies for this Stage must ensure Foundational Literacy and Numeracy for all children as this forms the basis of all further learning. Exposure to rich learning experiences in Language and Mathematics, and rich aesthetic and cultural experiences through art, crafts, music, dance, stories, and theatre would enable sound overall cognitive development. Multimodal forms of TLMs, adequate outdoor experiences, one-on-one Teacher attention, and physical wellness would also address the cognitive developmental needs of children at this Stage.

ii. Preparatory Stage: Pedagogy at this Stage will require a gradual move to more thinking and analysing after doing and observation, with plenty of material to engage with, repeat, and practise. This repeated practise will form the basis for study habits, independent thinking, and independent learning that is to come in the Middle Stage. Multimodal TLMs and one-on-one attention are still necessary to a good extent at this Stage, as these strategies will form a strong conceptual basis for students across Curricular Areas. Planning for field visits in the various subjects, apportioning sufficient time outdoors in a working week, encouraging students to demonstrate logic in their reasoning, encouraging thoughtful questioning, encouraging creative and artistic activity, learning skills to inquire through conversations with people, and reading/ referring to books are important pedagogical strategies in this phase.

iii. Middle Stage: This Stage often demonstrates the most accelerated learning possibilities — individual learning abilities and individual creativity begin to show sharply in distinction from others. This will require pedagogic attention, especially for those who struggle and for those who excel in their achievement levels given the context of group learning processes. Teaching students how to assimilate understanding and shifting from practical to theoretical concepts across curricular areas, demanding greater rigour in and capacity for working would be essential pedagogic considerations at this point.

With the introduction of newer Curricular Areas, it would be important to create adequate scaffolds for students to keep their interest and confidence in their intellectual capacities. Students’ capacities for abstract thinking and formulating one’s own innovative ideas improves markedly and Teachers can present challenging material that requires abstract reasoning and application. Rules for technology and media usage become necessary in this Stage. Teachers need to demonstrate in their teaching transactions (and explicitly teach) a discerning educational use of the internet and media gadgets in learning. This would require conversations about safe and healthy practices in using the internet, new media technology, and gadgets in the context of the curriculum.

iv.* Secondary Stage:* There exist ample possibilities for maturation in thinking, learning, practising, and creative expression in this Stage spread over four years of student life.

Teaching students how to independently assimilate understanding and encouraging abstraction and theoretical concepts across curricular areas, demanding rigour, and encouraging creativity and innovation in working, and presenting their views would be very important pedagogical considerations for Secondary students. Newer Curricular Areas and choices in specialisations begin at this Stage, and it would be important to help students make their decisions (in subject choices) and create adequate opportunities to sustain practice in these. Given their age and independence, technology and media use rules will need strong follow-up and reminders. As less supervision is possible, and the ‘discerning educational use of the internet and media gadgets in learning’ principle taught in the previous Stage is likely to wane, this will require repeated reminders. Caution against distractions while learning, cyberbullying, compulsive use, and many other unhealthy practices in using the internet will be required from Teachers, especially as students will be engaging with online research for learning much more in this Stage.

3.3.9 Overall Principles of Pedagogy