1. Rootedness in India and Indian Knowledge Systems

India has a rich cultural and ancient civilisational heritage with varied traditions within and

across local communities. Contemporary India is equally vibrant, taking its place in the modern

world. This vibrant national heritage — and the environment in which we live — influences the

way we think, speak, work, eat, wear clothes, interact with nature and with each other, schedule

our time, read, write, and learn. Our country is also home to deep knowledge and extensive

practice in a variety of disciplines and fields, from Language to Mathematics, Philosophy to Art,

grammar to Astronomy, Ecology to Medicine, Architecture to Agriculture, ethics to governance,

crafts to technologies, Psychology to Politics, literature to Music, and Economics to Education.

It is therefore important that all curriculum and pedagogy, from the Foundational Stage onwards, is designed to be strongly rooted in the Indian and local context and ethos in terms of culture, traditions, heritage, customs, language, philosophy, geography, ancient and contemporary knowledge, societal and scientific needs, indigenous and traditional ways of learning, etc. — in order to ensure that education is maximally relatable, relevant, interesting, and effective for our students. Stories, art, games, sports, examples, problems, and more, hence, must be chosen as much as possible to be rooted in the Indian and local geographic context. Ideas, abstractions, and creativity will indeed best flourish amongst our students and teachers when learning is thus rooted.

Hence, this NCF aims to be strongly rooted in India’s context and in Indian thought. This is manifested in the NCF in the following ways:

a. A holistic vision of education and its aims, from our ancient heritage to our modern thinkers, informs the overall approach of the NCF.

b. The vibrant epistemic approach of Indian schools of thought to knowledge and how we know.

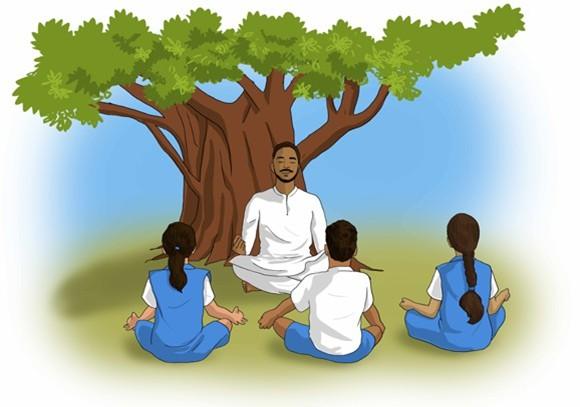

c. The core of the guru-shishya tradition as a base for the centrality of the Teacher-student relationship for effective learning; correspondingly, the tradition of dialogue and debate as the best way to acquire knowledge and wisdom.

d. The use of local resources for learning, including language, practices, experts, histories, environment, and more, as rich sources of illustrations or case studies.

e. The importance of the involvement of parents and communities in education.

f. Educational content, such as stories, art, games, sports, examples, and problems, chosen as much as possible to be rooted in the Indian and local geographic context, in order to maximise creativity, comprehension, relatability, relevance, and the flourishing of ideas in the classroom

g. The rich history of Indian contributions to various fields (also referred to as Indian Knowledge Systems) incorporated throughout the curriculum, as this not only develops pride and self-confidence, but also enriches learning in those areas. For example, Mathematics Education is enriched when students understand the multidisciplinary story of creativity in India in the discovery of the concept of zero, involving philosophy, linguistics, astronomy, and algebra; the approach to Environmental Education is deeply enriched by the range of nature-conservation traditions across India; and the approach to Values and Ethics is enhanced by its rootedness in Indian concepts and practices, such as respect and compassion for fellow humans and all creatures, embracing of diversity, and the spirit of service/seva, cleanliness/swacchata.

Section 1.1- NCF Anchored in the Indian Vision of Education

The Indian vision of education has been both broad and deep, including the idea that education must foster both inner and external development. Learning is not merely gathering information, but is about self-discovery and self-development, our relationships with others, being able to discriminate between different forms of knowledge, and being able to fruitfully apply what is learnt for the benefit of the individual and the society.

The rich heritage of ancient and eternal Indian knowledge and thought serves as a guiding light for this NCF. The pursuit of knowledge (Jnana), wisdom (Prajna), and truth (Satya) was always considered in Indian thought and philosophy as the highest human goal. The aim of education in ancient India was not just the acquisition of knowledge as preparation for life in this world or life beyond schooling, but for the complete realisation and liberation of the self. The Indian education system produced great scholars, such as Charaka, Susruta, Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Bhaskaracharya, Brahmagupta, Chanakya, Chakrapani Datta, Madhava, Panini, Patanjali, Nagarjuna, Gautama, Pingala, Sankardev, Maitreyi, Gargi and Thiruvalluvar among numerous others, who made seminal contributions to world knowledge in diverse fields, such as mathematics, astronomy, metallurgy, medical science and surgery, civil engineering, architecture, shipbuilding and navigation, yoga, fine arts, chess, and more. Indian culture and philosophy have had a strong influence on the world.

These rich legacies to world heritage must not only be nurtured and preserved for posterity, but also researched, enhanced, and put to new uses through our education system. Instilling knowledge of India and its varied social, cultural, and technological needs, its inimitable artistic, language, and knowledge traditions, and its strong ethics in India’s young people is considered critical for purposes of national pride, self-confidence, self-knowledge, cooperation, and integration.

The traditional Indian system of education, one of the oldest in the world, founded on the Teacher-student interrelationship, fostered holistic development and transmission of knowledge. Debates and discussions were the primary modes of learning and assessment. Teachers were often assisted by their senior students. Older students, more advanced in their learning, often taught younger, newer students. Collaborative and peer learning was encouraged.

Education focussed on the moral, physical, spiritual, and intellectual aspects of life emphasising values such as humility, truthfulness, discipline (and self-discipline, in particular), self-reliance, and respect for all. There was a strong emphasis on appreciating the balance between human beings and nature; it was understood that the individual’s well-being is dependent on the well-being of the world around them. Sources of learning were drawn from various disciplines — language and grammar, philosophy, logic, history, architecture, commerce, governance, agriculture, trade, archery. Creative arts developed a sense of aesthetics and sensitiveness to beauty in all aspects of life. Physical Education and Well-being was an important Curricular Area with learning of games, martial skills, and yoga, so as to include the body in a complete education.

Thus, education was seen as the integral growth of panchakosha (the five levels or parts of our being), an ancient Indian concept which explains the body-mind complex in human experience and understanding. (Please see Part A, Chapter 2 for details). This is also an eminently pragmatic perspective, achievable and complementary to life — developing good physical health and socio-emotional skills along with developing the ability to think and make ethical and rational choices and decisions in life, must occur in a holistic manner.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, many great modern Indian thinkers and personalities, such as Savitribai and Jyotiba Phule, Rabindranath Tagore, Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Jiddu Krishnamurti, emphasised the need for India to develop her own ‘national system of education’, with its roots in India’s intellectual and artistic heritage, but also integrating the important aspects of contemporary developments, in science and technology in particular (see NCF-FS for more details). Their philosophy of education also underpins this NCF.

Importance of Yoga Yoga today is too often understood as a set of practices centred on asanas (postures) and pranayama (discipline or expansion of the breath). But in the ancient Indian conception, yoga (literally, ‘union’) is vastly more: it refers to any of a number of systems of self-exploration, self-mastery, self-discovery — or indeed discovery of the Self (atman), which is how ‘yoga’ first appears in the Upanishads. To reach its ultimate objective, yoga (as in the celebrated Patanjali’s Yoga-sutras, a few centuries BCE) first insists on the stilling and detachment of the mind, with asanas and pranayama merely as aids to this discipline. Soon, other major forms of yoga are discussed (as in the Bhagavad-Gita), including jnana yoga or the yoga of self-knowledge, in which meditation usually plays an important part; bhakti yoga or the yoga of devotion and surrender to any form of the Divine; and karma yoga, where action and works are offered as a sacrifice, with no expectation of any fruit (niskama karma or desireless action). Many more paths of yoga have flourished, all of them sharing the same goal. On the way, some of their by-products, as it were, include peace of mind, unshakable calmness, control of emotions and desires, and a sense of focus and fulfilment. Yoga in its many forms has thus transformed the lives of millions, in India and across the world; its profound influence is perceptible in literature, art, and social life. This knowledge system may be said to be one of India’s most precious gifts to the world, and this informs the Indian approach to education and learning in very significant ways

Section 1.2 - Approach to Rootedness in India in the NCF

This NCF is anchored in our country’s understanding and experience of education and research across disciplines over thousands of years. This includes the full gamut of the country’s journey, from the knowledge, wisdom, and traditions of ancient India to the energy, vibrancy, and aspirations of contemporary India. This understanding and experience also includes local knowledge from all parts of the country, including local traditions and understandings from diverse and multiple communities.

The approach to rootedness in India in this NCF involves: (a) the Indian vision of the aims of education; (b) a vibrant epistemic approach; (c) a positive and nurturing Teacher-student relationship; (d) deep engagement of families and communities; (e) judicious use of local resources; (f) curriculum content carefully chosen according to the Indian and local context of the students; and (g) the incorporation of Knowledge of India — including Indian Knowledge Systems — in the curriculum wherever it is relevant, interesting, and beneficial.

1.2.1 Aims of Education

a. The NCF is rooted in the Indian vision of education, which emphasises the holistic development of every child. This includes physical development, socio-emotional development, intellectual development, spiritual growth, and development of values and dispositions.

i. All domains of development are seen as critical and equally important for human development and flourishing.

ii. The design of this NCF reflects the above principle with a range of Curricular Areas being part of school education — Mathematics, Languages, Science, Social Science, Art Education, Vocational Education, Physical Education and Well-being and Interdisciplinary Areas such as Environmental Education and Value Education.

iii. All Curricular Areas are seen as equally important for a child’s learning and development — there is no hierarchy across Curricular Areas.

iv. This equal importance is demonstrated by a common rigour in expected Learning Outcomes across Curricular Areas, the choice of content, the pedagogical approaches, the assessment strategies and, perhaps, most importantly, the time allocated to each of these areas in the school day.

b. One of the central aims of the Indian vision of education is character building. The NCF emphasises this through the development of values throughout the school years from early childhood onwards. Values and dispositions are developed through school and classroom culture and practices and through the learning of different subjects in the curriculum.

i. These include values that are an integral part of our tradition (e.g., seva, ahimsa, nishkam karma) and values that are part of our modern Constitution (e.g., commitment to equality, to justice, to the protection of the environment).

ii. Along with values, the NCF emphasises developing particular dispositions including a positive work ethic (e.g., being responsible, exerting oneself, pursuing quality and honesty in one’s work, having respect towards all manners of work).

This is further discussed in Part B, Chapter 2 on Values and Dispositions.

1.2.2 Vibrant Epistemic Approach

The theory of knowledge, or pramana-sastra, is one of the richest areas of classical Indian philosophy, spanning several centuries and rife with the liveliest debates. Indeed, claims about how we come to know is often the principal criterion that separates different schools or darsanas of Indian philosophy. Furthermore, questions about knowledge are almost inextricable from other fundamental questions about the nature of reality (metaphysics) and language.

These debates and approaches express themselves in the current scientific methods and the methods of the various disciplines; their nuances enrich our current thinking on ‘how we know,’ ‘what is it we know,’ ‘what is true,’ ‘what is adequate knowledge’, and more. Much of this nuance informs the Nature of Knowledge section of Curricular Areas (see Part C, Chapters 2 — 9).

It is important to note that the above methods of India’s intellectual tradition involved rigour and logic. To do justice to this tradition of questioning and debate, the NCF insists on the absolute authenticity of all educational material used in imparting rootedness in India, steering clear of the exaggerations and flights of imagination that have plagued numerous popular writings or websites, such as those insisting that ancient Indian savants were masters of aeronautics and nuclear weapons or knew the laws of quantum physics or string theory. Such claims are not only untenable but also end up discrediting and doing a disservice to the glorious and genuine intellectual heritage that Indian students are inheritors of

1.2.3 Teacher-Student Relationship — Effective Learning

One of the most significant principles of the Indian vision of education is the importance given to the relationship between Teacher and student. Based on this principle, this NCF emphasises a positive and nurturing relationship between Teacher and student that is enriching both for cognitive and socio-emotional-ethical development.

a. This positive relationship is developed mainly through Teachers getting to know each student individually, observing and listening to them carefully, encouraging their questions and responses, and recognising and responding to their thoughts and emotions.

b. Pedagogical approaches and classroom practices may alter as students grow and their ways of learning change, but irrespective of that, they are always based on this bedrock of a positive and nurturing relationship between Teacher and student.

c. In particular, this relationship will be anchored in the value system which the Teacher is expected to embody (see Part B, Chapter 2); this system rests on empathy and patience and promotes self-discipline in the student — a self-discipline of which the Teacher is expected to be an exemplar.

*1.2.4 Engagement of Families and Communities *

Another important aspect in the NCF is the role of families and communities in a student’s overall development and learning. The NCF is clear that Teachers and families should work together to understand each child better and together create a more positive experience for students. When families ask questions of Teachers and clarify doubts in their minds, they learn more about school processes. When Teachers understand a child’s home environment, they are able to plan better learning experiences for the student.

By sharing and working together, Teachers and families support the child’s development across all domains. This kind of involvement helps families support the learning experiences that happen in school through good practices at home as well. Families could also contribute to assessing the child’s progress and areas of need. They would also gain further confidence in their own parenting abilities through this process. These measures would help make the time at home and the time at school more synergetic, positive, and productive for the student.

*1.2.5 Local Learning Resources *

The use of locally rooted resources for learning is not only more cost effective, more eco-friendly, and more supportive of local communities, but it is also more pedagogically effective. It results in curricular content and pedagogy that is more relatable and interesting to the student, which in turn leads to better learning.

Teaching-learning Materials (TLMs) are thus most effective when they are locally sourced. This includes both physical items such as toys, books, games, sports equipment, vocational education equipment, art and craft materials, materials for science experiments, and local plants and flowers, as well as non-physical items such as stories, poems, songs, and festivals. Trips to places such as local parks, monuments, shops, businesses, and education institutions also are considered effective local learning resources at appropriate junctures in the curriculum.

1.2.6 Content Selected from the Indian Context

Learning happens best when it is situated and rooted in the student’s context. While contemporary ideas of teaching and learning are an important part of the curriculum framework, it is also extremely important that diverse experiences of children, their families, and their communities find a crucial place in the classroom. Ideas, abstractions, and creativity best flourish when learning is thus rooted.

a. The NCF foregrounds the child’s context as critical to learning all through the school years, with particular emphasis in the early years of a child’s life in school.

b. Local stories, songs, food, clothes, art, and music are an integral part of the learning experiences of students in school in order to ensure that education is maximally relatable, relevant, interesting and effective for children.

Thus, educational content, such as stories, art, games, sports, examples, and problems, will be chosen, to the extent possible, to be rooted in the Indian and local geographic context, to ensure maximal creativity, comprehension, relatability, relevance, and flourishing of ideas in the classroom.

1.2.7 Integration of Knowledge of India

Building both pride and rootedness in India is a fundamental disposition that is to be developed throughout school education. This happens primarily through building deep familiarity with India’s rich heritage, which includes India’s contributions to knowledge across all disciplines and fields of study from time immemorial, include some of the significant contemporary achievements. Building pride and rootedness in India is a focus across all Curricular Areas but should be achieved as a natural by-product of exposing the child to this heritage and ‘Knowledge of India.’

Knowledge of India will include knowledge, from ancient India and its contributions to modern India and its successes and challenges, and a clear sense of India’s future aspirations with regard to education, health, environment, etc. These elements will be incorporated in an accurate and scientific manner throughout the school curriculum wherever relevant.

In particular, Indian Knowledge Systems, including tribal knowledge and indigenous and traditional ways of learning, will be covered and included in mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, yoga, architecture, medicine, agriculture, engineering, linguistics, literature, sports, games, as well as in governance, polity, and conservation, where it is relevant and enriches learning. Tribal ethno-medicinal practices, forest management, traditional (organic) crop cultivation, natural farming, etc. will also be incorporated wherever possible and relevant. Thus, Indian Knowledge Systems here refer to all the systematised disciplines of knowledge that were developed to a high degree of sophistication in India, and also all of the traditions and practices, which various communities of India — including tribal communities — have evolved, refined, and preserved over generations. An engaging course on Indian Knowledge Systems will also be available to students in secondary school as an elective School culture and processes also help to strengthen knowledge of and connection to country, such as through everyday practices and activities like the School Assembly and through special events and festivals like Independence Day and Republic Day that reinforce pride in the country and its art and heritage, understanding of our struggle for independence, and the importance of preserving and protecting our independence.

Section 1.3 - Some Illustrations across School Stages and Curricular Areas

Learning about India, and thereby developing a pride and rootedness in India, is an integral aspect of this NCF. This is reflected throughout this document — as part of Aims of Education, Knowledge, Capacities, Values and Dispositions to be developed, Learning Standards at every Stage (in Curricular Goals and Competencies across curricular areas), as part of pedagogical processes across Stages, and as a fundamental principle of content selection through the Stages and across Curricular Areas.

Some illustrations are described below :

a. For children at the Foundational Stage:

i. One of the Curricular Goals at this Stage is learning the importance of seva. This is where children are first introduced to one of the most important Indian values and learn to help those in need — a value that will stay with them for life.

ii. Stories, music, art, games from the Indian and local context and from their families and communities are part of content used for teaching at this Stage. Children also have the opportunity to read and learn appropriate selections from India’s great repositories of stories, including fun fables, folk stories, and inspiring tales from the Indian tradition. Stories from the lives of Indian heroes and heroines of history are also seen as an excellent way to inspire and introduce core values in children.

b. At the Preparatory, Middle, and Secondary Stages, each Curricular Area takes a specific approach to embed rootedness in India based on the nature of the subject:

i. Art Education draws from ancient Indian texts such as the Natyashastra, Abhinaya Darpanam, Shilpashastra, Vastushastra, Chitrasutra, and Sangita-Ratnakara, which have codified and structured the elements, methods, and aesthetic principles of the arts. Through different Stages, students will develop knowledge of these elements and principles and a vocabulary of the arts used to describe and discuss artwork and their processes, e.g., sruti, naada, raaga, taala, laya, bhaava, alankaar, nritta, natya, pramaana, saahitya, gamak, meend, rasa. These concepts are to be introduced in such a manner that the student can experience them and experiment with them.

This will help students understand the unparalleled diversity and multicultural ethos of Indian artistic traditions through a consistent and meaningful engagement with local art, crafts, music, dance, theatre, puppetry, textile art, and so on. It also ensures that students are exposed to different genres of classical, folk, tribal, and contemporary artistic styles by providing adequate opportunities to view and be inspired by various aesthetic sensibilities and apply their imagination and expression while making their own artwork. The artistic processes of thinking, making, and appreciating will extend itself beyond the classroom to include the local community of artists, art administrators, and craftspeople, as well as a larger repository of art and culture through monuments, museums, archives, heritage sites, and other relevant cultural institutions and organisations.

At the Preparatory Stage, students are expected to observe their local art and culture, and practise basic art forms such as rangoli, and basic crafts such as clay work, pottery (without the wheel), puppetry, folk songs, folk dances, and so on. At the Middle Stage, students are expected to learn simple artistic processes that are associated with different art traditions and expand their knowledge of artists and art forms across their state and neighbouring states. They are also expected to draw comparisons regarding the stylistic features and social contexts of various art practices and architectural features of the region.

At the Secondary Stage, students are expected to broaden their art exposure to art traditions from different parts of India and analyse the similarities and differences, and the possible causes due to geographical or social contexts. They will also help them to apply this knowledge into their own art practice as they refine their crafting techniques and ideation skills. Class discussions, projects, and activities could include comparisons between different regional styles of music or dance or temple construction, so as to bring out not only their common, pan-Indian features rooted in the classical texts, but also their substantial regional variations. Such exercises will provide opportunities to introduce students to two fundamental principles of India’s art traditions, which are (1) faithfulness to classical concepts of aesthetics together with freedom to innovate; (2) free borrowings from folk to classical and vice-versa, resulting in mutual enrichment and endless diversity with an underlying unity.

ii. Technologies: As every other major ancient civilisation, India saw great advances in technologies, with some unique developments. Technology, however, cannot be defined here as the ‘application of scientific knowledge,’ since, more often than not, it precedes science; rather, it should be understood as the ways in which the living environment is altered by human activities and innovations. To drive this point home, it would be useful to first sensitise younger students (ideally through educational videos) to animal technologies, e.g., nest-construction by birds, dam construction by beavers, use of stones or sticks by apes, etc., as an illustration of the richness and complexity of the natural world.

Some of the early technologies in India, roughly in chronological order of appearance, include stone-tool making, hunting-tool making, agriculture (including animal husbandry), pottery, gemmology and bead-making, metallurgy, textile manufacture (including spinning, weaving, and dyeing) and various other crafts, transport technology (from the bullock-cart to transport of heavy loads, sailing, and shipbuilding), water management, construction, town-planning, faience and glass technologies, warfare (including weapon making), writing, cosmetics and perfumes, and more

Clearly it will not be possible or desirable to impart a detailed knowledge of these technologies to students. An overview with a few selected case studies will suffice. At the Preparatory and Middle Stages, a purely experiential approach to familiarise the child with a few technologies will work best. Examples could include playing with clay, replicating a water-management system on a small scale (perhaps in a part of the school campus), growing a few small patches of grains or pulses, extracting dye from some flowers and dyeing a white cloth, constructing a corbelled arch and comparing it with a true arch, playing with bricks of different proportions to show the efficacy of the modern (but also Harappan) proportions, constructing a miniature but fully functional bullock cart, understanding the difference between a river boat and a sea-faring ship (taking as starting points depictions of ships in Indian art, e.g. a painting in the Ajanta caves or a panel at the Sri Alakiyanampirayar temple at Tirukkurungudi), and so on.

At the Secondary Stage, more advanced technologies will be brought in, such as metallurgy, with stress on unique achievements such as wootz steel and rust-resistant iron. Their study will be multidisciplinary, since the former will highlight the popularity of this steel all the way to the Mediterranean world, while the latter will lead to a study of the tribal communities that perfected iron-extracting techniques, and their importance in Indian society. Excerpts from relevant texts will be used, again with care to point to their often cross disciplinary nature; for instance, a chapter on preparation of perfumes in Vaharamihira’s Brihat Samhita, mixing sets of basic ingredients in different proportions, provides a good example of combinatorics. Similarly, texts on shipbuilding connect with overseas trade and India’s considerable exports to many regions of the world until the colonial period; a manuscript on the construction of the gigantic Konark temple describes stone-lifting mechanisms which not only can be interesting objects of study, but it also records minute details of the work force engaged in the construction.

In summary, the study of a few early Indian technologies will not be so much about accumulating facts and figures as about understanding Indian society better.

iii. Science: The science curriculum will include references to both the everyday use of science in our lives as well as Indian contributions to scientific knowledge, such as those of astronomy mentioned below. While students will learn about the contributions of ancient Indian scientists, they will also engage with the contribution of modern Indian scientists to contemporary scientific knowledge as well as to nation building. This can include inspiring biographical sketches and pioneering discoveries of scientists such as J C Bose, P C Ray, Ramanujan, S N Bose, Meghnad Saha, C V Raman, A K Raychaudhuri, Harish-Chandra, Obaid Siddiqi, Bibha Chowdhuri, G N Ramachandran, Asima Chatterjee, Salim Ali, and many more.

In the Middle Stage, students will be introduced to Indian scientific ideas which can be explored through observation in the local community, e.g., students will explore local tools for measuring physical properties of matter, traditional Indian dietary and culinary practices, and diversity of food in India. They will connect concepts such as nutrition, sources of food, and impact of climatic conditions related to diversity of diets in the country. Activities could include cultivating a small plot of medicinal plants, documenting them and their medicinal properties.

At the Secondary Stage, students will be introduced to contributions made by ancient as well as contemporary India to scientific knowledge. They will examine the contributions of ancient India to science, indigenous practices related to health and medicinal systems, the basic principles and practices of a system such as Ayurveda, and contemporary Indian contributions to science and technology.

The case of astronomy requires a separate treatment:

iv. Astronomy: Although we often hear of developments in ‘Mathematics and Astronomy,’ Astronomy preceded Mathematics in most early civilisations, India’s included. A few thousand years ago, Vedic texts knew about lunar and solar years, equinoxes and solstices, solar eclipses, divided the year into six ritus or seasons of two months each, and gave the first list of 27 nakshatras or lunar mansions. Because of the need to keep time for agriculture (the proper time to sow crops and harvest them), for festivals, and for the proper conduct of rituals, calendrical astronomy became very precise in India, with several systems of intercalary months (adhikamasa) to compensate for the difference between the lunar and the solar years. Later, huge scales of time were conceived by Jain and other scholars to account for the cycles and duration of the universe. The solar zodiac with its 12 rashis was introduced, as well as the seven-day week, among other concepts. During the classical period, sophisticated techniques evolved to calculate the positions at any given time of the sun, the moon, or the five planets visible to the naked eye, and also the occurrences and parameters of solar and lunar eclipses.

Aryabhata gave a good approximation for the earth’s circumference, gave the correct explanations for eclipses, and proposed, among other theories to explain the sun’s apparent daily motion, that the earth was a sphere hanging in space, rotating upon itself. Later astronomers refined calculation methods, created highly accurate sine tables, and (as part of the Kerala School of Mathematics and Astronomy) had the planets revolve around the sun rather than around the earth.

The emphasis here will not be on the technicalities of such concepts, much less the calculations involved (except for a few simple ones), but on the ways in which ancient Indians viewed the cosmos and tried to make sense of it. The insistence on accurate and fast calculations rather than on theoretical models will also be shown to be a distinctly Indian approach to astronomy. A comparison of different regional calendrical systems can also be used to illustrate diversity with an underlying unity.

A more complete treatment of astronomy is found in Part C, Chapter 4 on Science Education.

v. Mathematics: India has a long history of contribution to mathematics in various domains of the discipline, beginning with geometry (for intricate constructions of fire altars, which led to the first general statement, around 800 BCE, of the Baudhayana Pythagoras theorem) and arithmetic (the basic operations and some early important equations and formulae). In their search for an efficient number system, Indian mathematicians used the zero not just as a placeholder (as the Mesopotamians also did), but eventually as a full-fledged number, which led to the development of the Indian numeral system, the most powerful numeration system in the world which is now used around the globe today and forms the basis for all modern science and technology.

Other major contributions included the discovery of the sine function by Aryabhata (of great application in astronomy and now throughout science), discovery of the negative numbers by Brahmagupta (with the rules for their basic operations), increasingly precise calculations of the decimals of π, with the first exact formula for π given by Madhava as an infinite series, foundational formulae in combinatorics and their interactions with linguistics and poetry, solutions to equations of several types such as single-variable quadratic equations and the Brahmagupta-Pell equation, and (again by Madhava’s school), the first expansions of trigonometric functions as infinite series, notions of their differentials, and other foundational elements of calculus.

Mathematics in this NCF makes a deliberate effort to introduce students to some of these major contributions by Indian mathematicians. At the Preparatory Stage, students will be introduced to the Indian origin of the Indian numerals and the decimal numeral system in use the world over. Students at the Middle Stage, and more so at the Secondary Stage, will be able to understand the development of important mathematical ideas over a period and locate the contributions of Indian mathematicians such as Baudhayana, Panini, Pingala, Aryabhata, Bhaskara I, Brahmagupta, Virahanka, Sridhara, Bhaskara II, Madhava, Narayana Pandita, and Ramanujan. At the Secondary Stage, students will learn about contributions of Indian mathematicians to advanced mathematical ideas including those in algebra, coordinate geometry, combinatorics, and calculus.

A more complete treatment of Mathematics is found in Part B, Chapter 3 on Mathematics Education.

vi. Social Science: One of the key Curricular Goals is for students to appreciate the importance of being an Indian (Bharatiya) by understanding India’s past and its rich geographical and cultural diversity. Indian contributions to democratic ideas which flourished in ancient, medieval, and the modern periods are also an important part of student learning.

At the Middle Stage, students will learn of the historical underpinnings which led to the formation of the modern Indian state and how ideas of peace, ahimsa, and coexistence have been part of Indian culture since ancient times; they will learn about codes of ethics set before rulers and elaborate democratic structures (e.g., assemblies, guilds, panchayats, and sabhas, such as that described in the Uthiramerur inscription) giving the society some freedom to self-organise; they will develop a perception of India as a civilisation rather than as a nation in the current limited sense. At the Secondary Stage, students will go into details to understand India’s past and appreciate its complexity, diversity, and unity brought about by cultural integration and the sharing of knowledge traditions across geographical and linguistic boundaries.

This is further developed in Part C, Chapter 5 on Social Science Education.

vii. Languages: Language education plays a crucial role in keeping students rooted to their country, as it allows individuals to connect with their culture, heritage, and society. Indeed, culture is largely embedded within languages. India is a country with a rich linguistic heritage, comprising scores of languages with a great literary heritage. Learning in the mother tongue or a familiar language at the Foundational Stage will keep students connected to their home and cultural heritage. R1, which is most often the regional language, will help students form a deeper understanding and connect.

Exposure to two other languages (R2 and R3) will help students to become multilingual, appreciate unity in diversity, and thereby help form a national identity.

This language curriculum framework will help individual students connect with their cultural roots and heritage by providing them with a deeper understanding of the language, literature, and cultural practices of their locality and of their country. It will help students appreciate the unity underlying diversity through observing shared concepts, motifs, perspectives, vocabularies, linguistic constructions, and cultural heritage in the country’s languages and literatures.

See Part C, Chapter 2 for further elaborations.

viii.Physical Education and Well-being: Sports and physical activities are an inseparable part of our culture — they unite us emotionally. India has very rich heritage of games and physical activity that developed across centuries e.g., yoga, wrestling (mallayuddha, kusti), malkhamb, handling of weapons such as bows (archery), maces, swords, and sticks, water sports, chariot racing, polo, different forms of martial arts (e.g., kalarippayattu), dance forms, hide and seek, and countless other games/physical activities.

Yoga has a special place in our knowledge systems and culture, and its benefits for all round development are well established. Yoga leads to peace and tranquillity, harmony and health, love and happiness, precision, and efficiency; although its physical aspect (asanas, pranayama) is the one most-often taught, its philosophical background, as a tool for self-realisation and self-fulfilment, should not be lost sight of. The approach in Physical Education and Well-being is to make these Indian games and physical/wellness activities an integral part of the curriculum across Stages.

ix. Interdisciplinary Areas: The Interdisciplinary Areas, by their nature, enable an understanding of the social and natural world. This understanding develops the capacity to identify core issues facing our society, and to act towards mitigating them to the extent possible.

An integral part of the Interdisciplinary Areas is Environmental Education. The focus of Environmental Education through school Stages is to develop capacities for understanding the need for and acting to maintain balance and harmony between human society (Samaj) and nature (Prakriti). This harmony is rooted in the Indian tradition of viewing human beings and nature as unconditionally interconnected. This tradition also makes no distinction between ‘animate’ and ‘inanimate,’ as it sees all elements of nature and the universe as imbued with consciousness. The constant efforts of human beings to preserve the environment, and therefore be preserved by it, are seen as a direct consequence of this worldview. This connect is emphasised not only in historical inscriptions and numerous texts, but also in the Constitution of India, which includes protection and improvement of the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and having compassion for living creatures among the Fundamental Duties.

In the Foundational and Preparatory Stages, students engage with their immediate social and natural environments and move towards the state, region, and country. Students are exposed to local stories, poems, narratives, folklore, histories, and games. They explore diverse socio-cultural practices, traditions, and festivals within their community, and connect these to the influence of the natural environment. Activities around plants, observing seasons or the weather can be supplemented by select videos of natural phenomena, wildlife, and more.

In the Middle and Secondary Stages, through an integrated approach with other disciplines as well as in the form of an essential area of study in Grade 10, students deepen their conceptual knowledge, and are able to use this to acquire an understanding of how Indian cultures and traditions evolved across the country. They also examine the relevance of traditional sustainable practices related to the conservation of resources and agriculture and engage with current efforts in the country towards mitigation of the effects of the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

Along with Environmental Education (Please see Part B, Chapter 3), Interdisciplinary Areas include a course of study on Individuals in Society in Grade 9, which aims to develop the capacity for ethical and moral reasoning among students. This capacity is enabled by the acquisition of traditional Indian as well as Constitutional values through the Foundational, Preparatory, and Middle Stages. Students engage with issues/events that are significant for the country, and also with current affairs that have far-reaching impact within their community and the world. These issues/events cover the sociocultural, political, economic, and environmental domains, and reflect both larger concerns that have persisted over a long period of time (e.g., equitable access to resources, preservation of local art and craft traditions) as well as current concerns (e.g., local elections, schemes for employment generation, ongoing efforts towards mitigation of impact of climate change, encouraging growth of tradition crops such as millets).

This NCF, therefore, aims to be rooted in the immense knowledge, rich culture, and traditions of India. It also ensures that our students build equal familiarity with contemporary India — our immense strengths, our rich diversity — and learn to respond sensitively and effectively to the challenges that we face as our country plays a greater role in the world.

Section 1.4 - Course on Indian Knowledge Systems

While the contributions to knowledge are best integrated in the whole schooling as described above, a special, engaging elective on Indian Knowledge Systems should be offered spread across Grades 11 and 12. Creative treatment and coverage of the matter would spark student interest. It could draw from current such courses, for example, a course entitled Knowledge Traditions and Practices of India (KTPI), which has been running for over a decade, with the following scheme:

| Grade 11 | Grade 12 |

|---|---|

| Philosophical Systems | Agriculture |

| Literatures (2 parts) | Architecture (2 parts) |

| Mathematics | Dance (2 parts) |

| Astronomy | Education |

| Chemistry | Ethics |

| Metallurgy | Martial Arts |

| Ayurveda (3 parts) | Language |

| Environmental Conservation | Other Technologies |

| Music | Painting |

| Theatre and Drama | Society State and Polity |

| Trade |

Each module includes a survey of the field, proposed activities and further readings, and a choice of selections from primary texts.

However, for this to happen, some of the modules would now be revised to a slightly more advanced level, since their basics will already have been integrated in earlier classes. This is the case especially of Mathematics, Astronomy, Chemistry, and possibly also Ayurveda, Environmental Conservation and Ethics, among others. The revision of the KTPI modules will be done taking careful note of the levels reached in those fields through the material integrated in the regular subjects and will ensure that students adopting these modules will be taken to a suitably higher level in both concepts and practices, including acquaintance with some primary texts, and will be exposed to a slightly wider range of material in those fields.

It should be emphasised that this elective course would be offered only as a means to deepen the student’s knowledge of the above disciplines. With this NCF, by the time students reach Grade 11, the regular curriculum will have ensured that they get exposed to some basic concepts and important practices; from Grade 11 onward, students not adopting this KTPI elective will get more such exposure through the regular curriculum, while those adopting this elective will have an opportunity to pursue those topics further.