1. Aims and Curricular Areas of School Education

Education must have clear Aims, and the curriculum and the overall education system must strive in every way to achieve these Aims. This first chapter of this NCF describes the Aims of School Education and outlines the elements of the curriculum that enable the achievement of these Aims. For our country's education, these Aims are derived from NEP 2020.

This chapter begins by reiterating the vision of Indian education as envisaged by NEP 2020, including the purposes of education and the characteristics of individuals that such an education would strive to develop.

The chapter then organises this vision provided in NEP 2020 into specific Aims of School Education that provides clear direction for the NCF, aligns its curricular elements, and also guides other elements of the education system. These Aims are to be fulfilled by developing appropriate Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions in the students which this chapter articulates.

School curriculum consists of all the deliberate and organised set of arrangements, mechanisms, processes, and resources in a school (of any kind) that are intended to help achieve the Aims of Education. These include the subjects that are taught, the pedagogical and classroom practices, books and other Teaching-Learning Materials (TLMs), examinations and other forms of assessment, and school culture and processes. The last section of the chapter gives a brief outline of these arrangements that are appropriate for achieving these Aims.

There are a range of matters that are not a part of the curriculum, but directly affect the curriculum in practice and therefore learning, such as the appointment of Teachers and their professional development, admission of students and the composition of students, engagement with parents and the community, and physical infrastructure. These aspects are thus touched upon in this NCF but are not addressed comprehensively.

Section 1.1 Vision of Education Drawn from NEP 2020

Education is, at its core, the achievement of valuable Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions.

Society decides the Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions that are 'valuable' enough to be developed through education, and so they are informed by the vision that the society has for itself. Hence it is through the development of Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions in the individual that education contributes to the realisation of the vision of a society.

The overarching vision of India is articulated in the Constitution of India and is also informed, therefore, by the civilisational heritage of India. Drawing from this vision of India, the vision of education in India is enunciated in NEP 2020 as follows:

This National Education Policy envisions an education system rooted in Indian ethos that contributes directly to transforming India, that is Bharat, sustainably into an equitable and vibrant knowledge society, by providing high-quality education to all, and thereby making India a global knowledge superpower.

[NEP 2020, The Vision of this Policy]

The vision is, thus, of an education system that contributes to the development of an equitable and vibrant knowledge society. Education can achieve this by developing appropriate desirable qualities in the individuals who participate in the education system as students.

These qualities of individuals, along with their contribution to society are further enunciated in NEP 2020:

The purpose of the education system is to develop good human beings capable of rational thought and action, possessing compassion and empathy, courage and resilience, scientific temper and creative imagination, with sound ethical moorings and values. It aims at producing engaged, productive, and contributing citizens for building an equitable, inclusive, and plural society as envisaged by our Constitution.

[NEP 2020, Principles of this Policy]

The aim of education will not only be cognitive development, but also building character and creating holistic and well-rounded individuals equipped with the key 21st century skills.

[NEP 2020, 4.4]

Thus, the development of well-rounded individuals capable of rational thought and action, equipped with appropriate knowledge and capacities, and possessing desirable moral and democratic values, is at the core of the vision of education.

Section 1.2 Aims of School Education

School Education must develop in students appropriate values, dispositions, capacities, and knowledge required to achieve the above vision of education. A curriculum, therefore, must systematically articulate what these desirable values, dispositions, capacities, and knowledge are, and how they are to be achieved through appropriate choice of content and pedagogy and other relevant elements of the education system, and present strategies for assessment to verify that they have been achieved.

Definitions Before we elaborate on the Aims of School Education, it is useful to clarify the meanings of the words — knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions as used in this document. Here is a brief explanation of what is meant by these words in this NCF:

a. Knowledge refers to descriptive knowledge, i.e., ‘knowing that’ — for example, knowing that the earth revolves around the sun or knowing that Mahatma Gandhi played a central role in India’s independence movement. A very large part of the understanding of the world is attained through this form of knowledge. This form of knowledge is expressed through theories, concepts, and principles. In a way, this form of knowledge reveals to us the truths about the world. While knowledge of this form might appear to be factual, the focus of acquiring such knowledge is not merely on remembering these facts, but also on the ability to think about why these facts are true, to inquire further, to connect together pieces of such knowledge, and to foster the development of new knowledge and insight and use such knowledge in life. For example, how can we know if the statement ‘Earth and other planets of our solar system revolve around the Sun’ is true? What are the sources of evidence? What are the methods of justification? Where can this knowledge be used? School education must focus on all these aspects of knowledge.

b. Capacities refer to procedural knowledge, i.e., ‘knowing how’ — for example, knowing how to communicate effectively or think critically or how to play Kho Kho. The abilities and skills acquired through this form of knowledge enable us to act based on our understanding. Usually, procedural knowledge is used in the context of embodied abilities, such as the ability to drive a car; however, problem solving and reasoning, for example, are procedural knowledge too. We refer to such broad know-how, such as critical thinking, problem solving, and effective communication as capacities, and these capacities can be broken down into narrower skills such as addition or decoding. Often, acquiring descriptive knowledge requires capacities too; for instance, in Science, the capacities and skills of observation and experimentation are central to building descriptive scientific knowledge. For example, without the skills of observation, it is difficult to truly justify that the Earth and other planets revolve around the sun. For a student to attain a capacity or a skill, the ability needs to be consistent and repeatable, and it also needs to be adaptable to different situations. For instance, to be skilled in making pots or performing addition, the student should be able to exercise that ability successfully not just once, but multiple times consistently and accurately, and should be able to work with different materials or numbers.

Capacities are broader and deeper than skills. A capacity often consists of multiple skills. Thus, skills are sub-elements of capacities. In other contexts or documents, ‘skills’ and ‘capacities’ may have been used interchangeably or ‘skills’ would have been used for what is classified as ‘capacities’ in this NCF. This NCF should be read with these distinctions in mind.

c. Values and Dispositions. Effective action needs strong motivation in addition to knowledge and capacities. Our values and dispositions are the sources of that motivation. Values refer to beliefs about what is right and what is wrong, while dispositions refer to the attitudes and perceptions that form the basis for behaviour. Thus, in addition to developing knowledge and capacities, the school curriculum should deliberately choose values and dispositions that are derived from the Aims of Education and devise learning opportunities for students to acquire these values and dispositions.

1.2.1 Aims of School Education in this NCF

The Aims of Education in this NCF are derived from the vision and purpose of education described above and are organised into five Aims.

These five Aims give clear direction to the choice of Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions that need to be included in the curriculum:

*a. Rational Thought and Independent Thinking/Autonomy: *Making choices based on rational analysis, creativity, and a grounded understanding of the world, and acting on those choices, is an exercise of autonomy. This indicates that the individual has gained the capacity for rational reasoning, critical thinking, knowledge with both breadth and depth, and discernment to understand and improve the world around them. Developing such independent thinkers who are curious, open to new ideas, think critically and creatively, and thereby form their own opinions and beliefs is thus a very important aim for school education.

*b. Health and Well-being: *A healthy mind and a healthy body are the foundations for an individual to pursue a good life and contribute meaningfully to society. School education should be a wholesome experience for students, and they should acquire knowledge, capacities, and dispositions that keep their bodies and mind healthy and free from any forms of abuse. Health and well-being thus also include, in particular, the ability and inclination to help ensure the health and wellness of others, of one's surroundings, and of the environment.

*c. Democratic and Community Participation: *The Knowledge, Capacities, and Values and Dispositions developed are to be oriented towards sustaining and improving the democratic functioning of Indian society. Democracy is not just a form of governance, but it is a 'mode of associated living,' a sense of collaborative community. The goals articulated in NEP 2020 point to the development of an individual who can participate and contribute meaningfully to sustaining and improving the democratic vision of India and the Indian Constitution.

*d. Economic Participation: *A robust economy is a critical aspect of a vibrant democracy, particularly for achieving dignity, justice, and well-being for all. Effective participation in the economy has positive impacts on the individual and on society. It provides material sustenance for the individual and generates economic opportunities for others in society, while also contributing to purpose and meaning for the individual.

*e. Cultural Participation: *Along with democracy and the economy, culture plays an important, if not central, role in the lives of all individuals and communities. Cultures maintain continuity as well as change over time. NEP 2020 expects students to have 'a rootedness and pride in India, and its rich, diverse, ancient and modern culture and knowledge systems and traditions'. Culture is thus not seen as merely an ornament or a pastime, but an enrichment

which equips the student (and Teacher alike) to face the many challenges of life, challenges which may be personal or collective in nature. Understanding the culture and heritage embedded in the family and community and relatedness to nature is at the core of cultural participation. Students should also acquire capacities and a disposition to contribute meaningfully to culture. In a globalised world, understanding and engaging with other cultures from a position of being confident and deeply rooted in Indian culture is very desirable.

A society with individuals who are healthy, knowledgeable, and with capacities, values, and dispositions to participate effectively and meaningfully in a community, economy, culture, and democracy would make for a pluralistic, prosperous, just, culturally vibrant, and democratic knowledge society.

Section 1.3 Knowledge, Capacities, and Values, and Dispositions

The five Aims of Education as articulated in the previous section would be achieved by schools by developing relevant and appropriate knowledge, capacities, values, and dispositions in their students. The Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions that are to be developed in students to achieve the five Aims are described this section.

1.3.1 Values and Dispositions

India has been a significant contributor to the discourse on values and of their practice, from ancient times to today. The exploration of humanistic and pluralistic values is embedded in our civilisational and local cultural traditions, and our Constitution is a beacon of democratic values. NEP 2020 derives its values from our heritage and traditional sources, from broad humanistic values, and from our Constitution.

Attaining the aims of rational thinking, health and wellbeing, and democratic/economic/cultural participation require the following broad categories of values in individuals and in society:

a. Ethical and moral values. The 'values of seva, ahimsa, swacchata, satya, nishkam karma , tolerance, honest hard work, respect for women, respect for elders, respect for all people and their inherent capabilities regardless of background, respect for environment, etc. will be inculcated in students.' [KRCR 2019, 4.6.8.2] These values are virtues that students need to develop, and these are beneficial to the individual, in terms of their health and well-being, as well as to society as a foundation for democratic values.

b. Democratic values. These values include 'democratic outlook and commitment to liberty and freedom; equality, justice, and fairness; embracing diversity, plurality, and inclusion; humaneness and fraternal spirit; social responsibility and the spirit of service; …commitment to rational and public dialogue; peace; social action through Constitutional means; unity and integrity of the nation…' [KRCR 2019, 4.6.8.3]

*c. Epistemic values. * These are values that we hold about knowledge and truth. Developing a scientific temper is as much a value orientation towards the use of evidence and justification, as much as understanding current scientific theories and concepts.Inculcate scientific temper and encourage evidence-based thinking throughout the curriculum'. [KRCR 2019, 4.6.1.1] Recognising the sources of knowledge and truth in different domains and having the integrity to adhere to the relevant and acceptable methods of finding the truth is an important value orientation. Along with the above values, the NCF would intend to develop the following dispositions in students:

*a. A positive work ethic. *Any form of achievement, if it needs to be achieved through just and equitable means, requires honest, deliberate, and sustained work. This includes learning achievements too. While hard work and perseverance are important, being responsible and taking up and completing an honest share of work are equally so, especially in situations where work is accomplished collectively. Respect towards all modes of work - with hands, with technology, household work, office work, outdoor work, or factory work - is very desirable. Developing these dispositions in students becomes a very important goal for school education

*b. Curiosity and wonder. *Curiosity and wonder are at the core of learning, and, with this disposition, students can become lifelong learners. The very young child comes with natural curiosity to engage with the social and practical world around them. This needs to be sustained, extended, and expanded. If knowledge needs to be active and alive and not passive and inert, students have to approach knowledge with curiosity and wonder. The world around us is a limitless source for developing this disposition.

*c. Pride and rootedness in India. *The Aim of cultural participation indicates that students should develop dispositions that make them rooted in the overall Indian context and in their local context, while being an engaged citizen of the world.

The vision of NEP 2020 states that The vision of the Policy is to instil among the learners a deep-rooted pride in being Indian, not only in thought, but also in spirit, intellect, and deeds, as well as to develop knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions that support responsible commitment to human rights, sustainable development and lifestyles, and global well-being, thereby reflecting a truly global citizen.

The notion of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam , the world as one family, emerges from this rootedness along with a sense of justice, service, self-discipline and self-fulfilment, compassion and empathy, and acceptance of unity in diversity. With the vibrancy, range, and the depth of our culture and heritage, Indians must engage with the rest of world with assurance and confidence and with empathy and openness.

* 1.3.2 Capacities *

While values and disposition are sources of motivation to act, acting effectively requires students to have specific capacities. These capacities can be developed through deliberate and conscious engagement and practice. The Aims of Rational Thought and Independent Thinking, Health and Well-being, and Democratic/Economic/Cultural Participation necessitates the following broad set of capacities.

a. Inquiry. To act rationally, we need an understanding of the world around us. This understanding requires the abilities of observation, collection of evidence, analysis, and synthesis. Experimentation and innovation are the practical aspects of this capacity. Beyond these general capacities of inquiry, there are discipline-specific skills, such as laboratory skills or field techniques, which assist in the process of inquiry. These capacities of inquiry are fundamental in achieving all five Aims.

b. Communication. The abilities to listen, speak, read, and write in multiple languages are also indispensable capacities. To be able to express oneself - both orally and in writing – in a lucid, well-articulated, and coherent manner – is very important throughout life; this also includes the skilled use of digital media. The ability to use varied forms of communication in different contexts that are appropriate for the intended audience is very valuable in achieving all the Aims.

c. Problem Solving and Logical Reasoning. The ability to formulate problems, develop many alternative solutions, evaluate different solutions to choose the most optimal solution, and implement the solution is again indispensable in achieving all five Aims. Problems that require quantitative models require the mastery of various mathematical procedures, starting from simple arithmetic skills of addition and subtraction to more complex solving of algebraic equations. The use of computational models for solving problems would require computational skills. Skills for logical reasoning include constructing and evaluating arguments, both formally and informally.

d. Aesthetic and Cultural Capacities. The Aims emphasise creativity and aesthetic and artistic expression. Creating works of art requires skills specific to different forms of art – visual arts, music, dance/movement, and theatre. Culturally relevant skills in art forms enable effective cultural participation. Aesthetic and cultural capacities also help strengthen creativity across domains and thus strengthen the capacities of inquiry and problem solving and also improve language and communication, and are also, therefore, critical in achieving all five Aims. Artistic skills further enable students to effectively express emotions and thoughts through art, thus improving their sense of health and well-being.

e. Capacities for Health, Sustenance, Self-management, and Work. Developing skills and practices that enable students to lead a healthy life is one of the important Aims. Developing strength, endurance, and perseverance is not just in terms of physical capacities, but also related to the capacities of the mind. Capacities of self-management, including emotional capacities are important. Such capacities are foundational for not just well-being, but also contribute positively towards autonomy and democratic participation. These capacities, along with the disposition of a positive work ethic, should enable students to participate in the economy meaningfully and significantly.

f. Capacities for Social Engagement including Affective Aspects. Empathy and compassion are not only values or dispositions; these are capacities that are developed through deliberate practice. Cooperation, teamwork, and leadership are fundamental capacities for social engagement. Along with the capacities for logical reasoning and problem solving, these capacities are crucial for democratic participation. And these capacities have an affective (emotional) aspect – which too needs to be addressed.

Indeed, all capacities enumerated above promote the five Aims - Rational Thought and Independent Thinking, Health and Well-being, and Democratic/Economic/Cultural participation. With the desirable values and dispositions and equipped with appropriate capacities, it is expected that students will live healthy, independent lives and participate actively in the community, economy, culture, and democracy. But these values and capacities do not operate in a vacuum; they must be based on a clear understanding of the world. This understanding is gained through the achievement of knowledge in breadth and depth.

1.3.3 Knowledge

Education is often thought of and practised only as the acquisition of knowledge. While this is an inadequate view, without a doubt, knowledge has a central role and place in education. Knowledge about the self, others, the social world, and the physical and natural world is at the base of all the five Aims of Education. The achievement and practice of values, dispositions, and capacities, which are also equally important aims of education, are not primarily about acquisition of knowledge, but intrinsically depend on knowledge.

The vast and ever-increasing knowledge of humanity is and should be made available to all. All that humans know has developed over history through specific modes of inquiry — both through more formalised methods of knowledge development, and also through less formalised and more experiential, organic approaches. The theories and concepts within a mode of inquiry have emerged sometimes through incremental explorations of a whole community, and sometimes through dramatic insights of a few remarkable individuals. Equally, or perhaps even more so, knowledge has developed through the accumulated experience and wisdom of ordinary people. There are no neat divisions on how human knowledge develops — formal inquiry and knowledge through life experience merge and reinforce each other. Our accumulated and expanding knowledge is a human heritage and it is the responsibility of schools to share this heritage with every new generation.

Given the centrality of knowledge to education, there are many matters related to knowledge that have a deep implication on curriculum. Some of these matters are:

• How does something become knowledge? In other words, how do we know that something is true and valid?

• How do we search for, discover, and build more knowledge?

• What are the interconnections within knowledge? What knowledge becomes the basis for some other knowledge and why?

• Can there be contradictions in knowledge? Why and how do they arise? How are these resolved?

• How is knowledge acquisition by humans influenced by context and by values?

• What are the ethical and moral issues associated with the pursuit of knowledge?

These matters may seem esoteric and more suitable for a Philosophy book than for school

education. But the reality is that Teachers, curriculum and syllabus developers, and others

grapple with these very issues in school education every day. The implications of these matters

directly influence many aspects of the curriculum. For example:

• What should be taught? What should be the content of subjects?

¶ What ensures that content is true and valid?

¶ What should be included to give adequate understanding of a subject area?

¶ What should be the sequence of teaching concepts, considering the interconnections?

¶ How should the developmental stage of the students be accounted for?

¶ How should knowledge that is yet uncertain or has many alternative perspectives be

included?

• How should we teach? How should we assess? How can we make TLMs effective?

¶ Which pedagogical approach is best for which kind of knowledge? What are the options?

¶ How should we teach so that the integrated, holistic nature of human knowledge and

experience is developed?

¶ How should we teach so that students form a full picture and are also able to apply their

knowledge?

¶ How do we know that a student has truly ‘learnt’ something?

¶ What TLMs are best suited to what knowledge? How should we develop them?

• What are the ways to ensure that students learn existing knowledge while also discovering

new things?

¶ Since no one can be taught ‘all the knowledge,’ how can students be encouraged to

continue to search for and learn existing knowledge from the wider world, at present

and later in their lives, and also gain the capacity to develop new knowledge?

• What kind of knowledge is required to develop the capacities and values that are aimed for?

¶ How are moral and ethical capacities best developed?

¶ How are cognitive and socio-emotional capacities, such as critical thinking, empathy, and

wonder, best developed?

While this is a long list of direct curricular questions that arise from questions related to the

nature of knowledge, this is not an exhaustive list.

We must also note that many of these matters have subject-specific implications in school

education. For example, the nature of knowledge in Mathematics is such that many topics must

have a certain sequence; the nature of knowledge in Social Sciences is such that it requires many

perspectives; and the nature of knowledge in Science is of a kind where learning by doing

experiments is particularly useful.

Thus, in this NCF, each subject chapter (as in Part C, Chapters 2-9) has a section on the ‘Nature of Knowledge’ particular to that subject. However, a vast amount of human thought and discourse related to knowledge has a common base across all spheres, including school education. The subsection that follows discusses this common base.

1.3.4 Knowledge — the Foundations

India has a vibrant tradition of thought and discourse on the theory and practice of knowledge. Without doubt, other cultures too have had rich traditions on this matter – both widely recognised, such as the Greeks and the Japanese, and the less recognised, such as the Native Americans. However, the richness, nuance, and range of Indian thought on this matter is very special, if not unique.

If we consider the most current thoughts on knowledge, anywhere in the world, one can often observe similar ideas in Indian thought from two millennia earlier – in many senses directly anticipating it and perhaps having deeply influenced it through cultural transmission. Thus, it is both important and useful to ground our thinking and practice on this Indian heritage. The nine ‘Schools of Thought’ in Indian philosophy (see Box 1.3i) form an important source of views and discourse on the nature of Knowledge.

Indian Schools of Thought — a Brief Glimpse There are nine main darsanas or world views (sometimes translated as ‘schools of thought’) in classical Indian philosophy: 1) Nyaya; 2) Vaisesika; 3) Sankhya 4) Yoga 5) Mimamsa; 6) Vedanta; 7) Buddhist; 8) Jaina; 9) Lokayata/ Carvaka all of which date back to at least a few centuries BCE

The Nyaya darsana was founded by the sage Gautama. This darsana was primarily occupied with formal reasoning, rhetoric, and epistemology, although it also made substantial contributions to metaphysics. The Vaisesika system was founded by Kanada. This darsana was known for its efforts to make sense of the material world, the various categories and components of matter and their properties, behaviour, etc. It has similarities with Nyaya, but its focus was more on metaphysical questions and less on principles of reasoning. At a later stage, some Nyaya and Vaisesika authors became increasingly syncretistic and viewed their two schools as sister darsanas.

Sankhya is the oldest of the systematic schools of Indian philosophy and dates back to the Vedic period. Its views are heavily based on the Upanisads. Sankhya argues for a dualistic ontology comprising Prakrti (nature) and Purusa (person). Just as Nyaya and Vaisesika are sister darsanas, so too are Yoga and Sankhya. Yoga accepts the Sankhya dualism and calls on the practitioner to disentangle the Purusa from the Prakrti, thus freeing the former to achieve its full dimension and powers. Their main difference becomes evident in the relative importance of mind and body, as well as in their accounts of how liberation (moksa) is attained.

The Mimamsa darsana concerns itself largely with ethical questions and takes as its main goal the elaboration and defence of the contents of the early, ritually-oriented part of the Vedas. This school also contributed a great deal to the philosophy of language. Unlike the four darsanas discussed previously, Mimamsa holds that the Vedas are epistemically foundational. This founding principle is shared by the Vedanta darsana. The Vedanta darsana concerns itself, however, with the latter part of the Vedas, where the principal concern is knowledge and moksa.

The Lokayata were materialists who denied the existence of an atman that persisted through many lives. The Buddhists denied the existence of such a thing as a coherent self. The Jainas argued for a variety of jivas, so that even nature and not just humans and Gods — was seen as ensouled.

Despite this apparent split, all these different darsanas influenced and were influenced by each other and, for the most part, classical Indian philosophy is best seen as a series of complex dialogues within and between these darsanas. For example, Jainism was very influential for the Yoga darsana. Nyaya and Buddhist thinkers were in continual, spirited dialogue. The Nyayasutra itself is one of our best sources for Lokayata thought and presents and responds to a series of Lokayata objections.

Beyond these nine schools, many others developed, which is a reflection of the acceptance of multiple paths and the freedom of thought that prevailed in early India.

The theory of knowledge, or pramana-sashtra, is one of the richest areas of classical Indian philosophy, spanning several centuries and with the liveliest of debates. Indeed, claims about ‘how we come to know’ is often the principal criterion that distinguishes different schools or darsanas of Indian philosophy. For example, the Vaisesika philosophers argue that validity arises from the right source, whereas the Yogacara argue that validity is that which guides successful action. Furthermore, questions about knowledge are also related to other fundamental questions about the nature of reality and language. The pramana-sashtras are a key basis for Indian Knowledge Systems and are described in greater detail below.

1.3.4.1 Pramanas — Vibrant Tradition of Epistemology

While there are many similarities and vibrant dialogues amongst them, these different darsanas (See Box 1.3i) represent a wide range of views on what constitutes an appropriate pramana (evidence/proof/justification) or basis for knowledge. The main pramanas used are a) perception; b) inference; and c) testimony.

A brief description of the range of views on this matter follows, merely to give a flavour of the vibrant nature of this Indian discourse.

a. The different darsanas are all in agreement about the fact that we attain knowledge through perception (pratyaksha). However, there are considerable debates about the nature of perception. According to the Nyaya, all perception requires a sensory connection with an object that gives the perception its content (nirakara-vada); for instance, in Nyayasutra, it is stated ‘Perception is an awareness which, when produced from the connection between sense organ and object, is non-verbal, accurate and reliable, and definite.’

According to early Mimamsa, perception essentially happens through language; there is no such thing as concept-free perception. Not only do later Mimamsa thinkers, such as Kumarila Bhatta, disagree with this, the Yogacara do as well.

Many Buddhist thinkers argue that we do not perceive any object at all, but only bundles of sense data, such as colour, sound, and smell, in opposition to the realist Nyaya doctrine.

b. Different kinds of inferences were considered in pramana-sashtras.

i. Anumana: Using inferences to come to new conclusions from observations is one way of

coming to know.

ii. Upamana: Knowing through analogy and comparison is upamana. Relating to existing

knowledge and identifying the similarities and differences and, thus, coming to know

new things or experiences is another valid way of knowing.

iii. Arthapatti: Knowing through circumstantial implication is arthapatti.

iv. Anupalabdi: Perception of non-existence is considered a valid form of knowledge.

Observing that the well is empty of water is knowing something about the well. People

have come to significant conclusions because ‘the dogs did not bark that night.’

In general, inference is accepted as a secondary knowledge source in cases where what is known cannot be evident through perception alone. Unlike western philosophy, logic is an essential part of the theory of knowledge in the Indian tradition and not a separate discipline.

Its value is in its ability to help us arrive at truth. Logic and inference are also understood in a much broader sense, including not just rules of reasoning, but also as a psychological process that allows us to know, via hetu (a sign), indirectly.

The Nyaya-sutra has many examples of how we come to know through hypothetical induction. The Vaisesikasutra spells out how we can infer through extrapolation, e.g., through the presence of its horns, we can know through inference the presence of an entire cow. It provides us with a series of rules for when such extrapolation is warranted. On the other hand, some in the Lokayata tradition deny that we can ever know via inference, because inference is prone to mistakes.

c. Testimony (sabda) is a highly debated source of knowledge. Not just Lokayata, but also Vaisesika and Buddhist schools, deny that testimony in general can be an independent source of knowledge. The Lokayata accept only perception, whereas Buddhism is founded on the idea of experience and reasoning as the only ways of learning anything, while Nyaya and Mimamsa thinkers argue for use of testimony under specific conditions and from specific sources.

This brief glimpse points to the significant contribution of Indian thinkers to the field of epistemology and the understanding of the nature of knowledge.

1.3.4.2 Implications on Curriculum

The depth and range of thought on the matter of knowledge in India, including contemporary Indian thought, along with relevant thinking from across the world, must inform our curricula. This is operationalised by a method of organising knowledge which is on sound foundations and is useful for curriculum.

Informed by these range of discourses, school knowledge has, for practical purposes, been organised into different kinds or forms. Each kind has its own conventions on:

a. the scope of inquiry (what questions to explore)

b. specific ways of giving meaning to concepts

c. specific methods of validating the truth of the claims being made (how to answer those questions)

Each form of knowledge has distinct but related methods of reasoning and justification, procedures and protocols, and what is to be admitted as evidence. In a way, each form of knowledge has its own kind of ‘critical thinking’ and its own ways of being ‘creative.’

Mathematics, the Sciences, the Social Sciences, the Arts and Aesthetics, and Ethics are some of these kinds of knowledge that have their own sets of concepts and theories through which we make meaning of our experiences. These forms give clear direction as to what knowledge all students in schools should acquire. They help, in part, determine the different Curricular Areas of this NCF.

Through engagement with these kinds of knowledge, students develop disciplinary knowledge. While the capacity for problem solving depends heavily on such disciplinary knowledge, often real-life situations pose problems whose solutions are informed by many disciplines that need to be integrated. For instance, the problems of sustainability and climate change are not merely informed by the Sciences, but also by our understanding of the Social Sciences and Mathematics. Thus, engagement with interdisciplinary knowledge becomes an important goal for school education along with disciplinary knowledge.

Section 1.4 Towards a Curriculum

Schools must arrange to develop in students the desirable Values, Dispositions, Capacities, and Knowledge. As mentioned before, these arrangements range from the selection and appointment of Teachers to school culture and the actual subjects that are taught in the school.

The curriculum includes all those arrangements that directly impact the engagement and learning of students. While the curricular imagination for a school is often restricted to the arrangements of classroom interactions, the school culture, practices, and ethos also play a very important role, both in enabling a positive learning environment as well as promoting desirable values and dispositions.

In this section, the specific curricular arrangements that schools must organise — so that students gain the desired Values, Dispositions, Capacities, and Knowledge — are explored.

1.4.1 School Culture

Schools achieve educational aims not just through teaching within the confines of the classroom, but also through the inclusion and assimilation of the students into the extant culture and ethos of the school.

Values and dispositions, in particular, are deeply influenced by immersion in the school ethos and culture, and so forms an integral part of the curriculum. Thus, to develop specific values and dispositions, there has to be a deliberate shaping of the school culture and ethos. In the absence of such deliberate shaping, whatever be the school culture that has emerged will have significant influence on the students, which may even be at odds with the Aims of Education.

Values and dispositions are also profoundly shaped by the family, community, religion, local and popular culture, art, literature, media, and other influencers. The school is somewhat different from many of these influencers because it has clearly articulated goals for the values and dispositions and presents the opportunity to work towards them systematically and methodically. Hence, it is equally important for a curriculum framework to explicitly articulate the arrangements and organisation of the school in terms of its culture and ethos that would promote the desired

values and dispositions. This NCF has made specific recommendations for school culture and ethos in Part D, Chapter 1.

1.4.2 School Processes

In addition to school culture, more formal and well-defined school processes have a significant role to play in both ensuring the smooth functioning of the school, as well as enabling the achievement of Curricular Goals. Processes for maintaining academic accountability towards achieving the aims, both from the Teachers and students, are important to be articulated, understood, and followed. Thoughtfully designed school processes are required to address simpler matters, such as maintaining the cleanliness of the school premises, and more complex matters such as responding to Learning Outcomes of students. This NCF makes specific recommendations related to school processes in Part D, Chapter 2.

1.4.3 Curricular Areas

எண் ணென் ப ஏனை யெழுத்தென் ப இவ் விரண் டுங்

கண் ணென் ப வாழும் உயிர்க்கு

Ennenpa enai yeluttenpa ivvirantun kannenpa valum uyirkku.

The learning of numbers and letters –

these are the two eyes of the living person.. [Tirukkural 392, Tiruvalluvar. Transliteration and translation by Narayanalakshmi] Ancient Indians had clear conceptions of what is valuable in education. As the above couple from the ancient Tamil poet Tiruvalluvar indicates, Language and Mathematics were seen as two eyes through which we make sense of the world. It is not surprising then that Language and Mathematics continue to be two of the most important Ccurricular Areas, even many centuries since this verse was written!

To achieve the aforementioned Knowledge, Capacities, Values, and Dispositions, the curriculum also needs to enumerate specific Curricular Areas. This division is not just a pragmatic necessity for organising classrooms, timetables, and Teachers.

While pragmatic considerations are equally relevant, these distinct Curricular Areas have an internal logic. The internal logic is determined by the conceptual structures and methods of inquiry that are specific to that ‘kind of knowledge.’ Each Curricular Area has interconnections within, arising from specific methods used to arrive at the knowledge, as well as aspects of and perspectives on the world that they highlight. Pragmatically, each Curricular Area leads to its own time slot in the timetable, as well as its own textbooks and other TLMs, Teacher allocations, and so on.

This NCF uses ‘Curricular Area’ as a broader category, to distinguish it from ‘discipline,’ ‘field,’ and ‘subject’: • ‘Discipline’ is a branch of knowledge — for example, sociology, economics, biology, mathematics. • ‘Field’ is used with the connotation of being focussed on application and use in the world and is often informed by multiple disciplines — for example, engineering, public health, sustainability. • ‘Subject’ is most often used in the context of schools — and is what students ‘study’ — it could be a discipline, a field, or a combination or part thereof. • ‘Curricular Area’ is a group of disciplines and/or fields with an underlying logic for grouping them together — for example, Science, Social Science. In this NCF, ‘subject’ will continue to be used for what the students’ study. Subjects will be grouped within ‘Curricular Areas’ in the NCF for practical purposes. ‘Disciplines,’ ‘fields’ may be used only to refer to the sources of knowledge for the construction of subjects, where required. The usage of this terminology (and nested hierarchy) is not a conceptual matter but is merely for the ease of communication of the design of certain critical aspects of this NCF.

1. Languages: Language is not just a medium of thinking, nor merely a tool for acquiring different forms of understanding. Language education makes effective communication possible and equally develops aesthetic expression and appreciation. Analytical reasoning and critical thinking are very closely linked with language use, and these are valuable capacities to be developed through the learning of languages. Particularly in the context of India, multilingualism, sensitivity to and appreciation of a diverse set of languages, and cultural literacy and expression are desirable outcomes of language learning as articulated in NEP 2020.

2. Mathematics and Computational Thinking: Mathematics is a form of understanding the world through patterns, measurements, and quantities. Mathematics education also develops capacities for problem solving, logical reasoning, and computational thinking.

3. Sciences: Science (also sometimes referred to in this NCF as the Natural Sciences) is a form of understanding the natural world. It has its own specific methods of inquiry, reasoning, theories, and concepts. Beyond aiding in gaining an understanding of the natural phenomena around us, Science Education helps develop rational thought and scientific temper.

4. Social Sciences: Social Science (which, in this NCF, includes the Humanities) aims to understand the human world. The methods of inquiry in the Social Sciences are evidence based and empirical through specific methods of reasoning. Social Science also promotes rational thought and scientific temper, as well as an understanding of one’s community and society. Additionally, subjective experiences are analysed through interpretation and reflection. Social Science helps in promoting students’ effective cultural/economic/ democratic participation.

5. Art Education: Art is a form of understanding through which we make aesthetic sense of our experiences. Engagement with art also builds our capacities for being creative across subjects and develops cultural sensibilities. Learning art allows students to engage and participate meaningfully in our culture and, because art involves the physical, emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual parts of ourselves, learning it also helps contribute to the student’s general well-being and integrated development.

*6. Interdisciplinary Areas: *While forms of understanding give disciplinary knowledge and depth, interdisciplinary knowledge and thinking is also an important goal as discussed earlier. Engagement in interdisciplinary areas develops capacities for interdisciplinary thinking and problem solving. This Curricular Area therefore complements the disciplinary thinking of the aforementioned five disciplinary Curricular Areas.

Beyond these forms of understanding, Physical Education and Vocational Education are important Curricular Areas. These areas become important due to the specific Curricular Aims of health and well-being and economic participation. NEP 2020 has given specific directions for Physical and Vocational Education.

7. Physical Education and Well-being: Physical Education and Well-being focusses on developing capacities for maintaining health, well-being, and emotional balance. Through engagement in sports, games, yoga, and other techniques, important ethical, moral, Constitutional, and democratic values are also developed.

8. Vocational Education: Vocational Education intends to develop capacities for sustenance, work, and economic participation. It also develops values and sensibilities towards physical work and an appreciation of the dignity of all labour. NEP 2020 has given a strong emphasis to giving vocational exposure and developing vocational skills from the very early stages of school through higher education.

These eight Curricular Areas have their own specific Learning Standards, and have specific recommendations for content selection, pedagogical approaches, and methods of assessment.

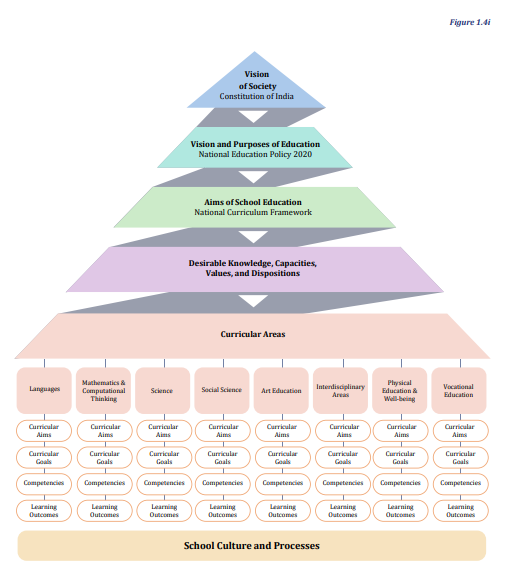

These details have been outlined in Part C, Chapters 2 to 9. Figure 1.4i depicts how the NCF — which includes the Curricular Areas (its goals, pedagogy, books, assessment etc.), school culture, and school processes necessary to achieve Aims of School Education — flow from the vision of society that is envisaged in our Constitution.